A bookstore; a ballad; and Blondie’s masterpiece, Eat to the Beat.

Collectively casting a halo

I’m All Lost In…

the 3 things I’m obsessing over THIS week.

#37

1) My great friend Valium Tom, aka Tom Nissley, celebrated the 10th anniversary of his easy going, literary bookstore, Phinney Books, this week. He marked the occasion by inviting the community to the store after business hours for wine, beer, crudités, and sliders (tofu versions available for the vegans, which seemed to be me and Tom’s wife Laura).

There was no book selling allowed, which drew out Tom’s delightfully-chatty- on-this-evening, longtime staff—Kim, Liz, Haley, Anika, Doree, and Nancy—from behind the counter and into the cozy, throne-sized leather chairs usually reserved for customers.

Tom, center, thanking his adoring customers.

It’s no surprise that a warm soul like Tom has assembled and fostered such an exceptional cast of dedicated squares. (Tom noted, in his neighborly remarks that, turning job applicants away on the daily, he hasn’t had to hire any new staff in six years.) But what a gas to watch them let their hair down and debate book recs over wine; Miranda July’s All Fours was the current staff favorite, although contrarian Liz, obviously revered by her colleagues (and Tom) as Phinney’s quirky conductor (to Tom’s composer), was not convinced.

The place was overflowing with customers-turned-summer-evening-cavorters, all of them talking books as well per the flurry of list making going on: there were cards to fill out. List the Top 10 Books You’ve Read over the last 10 years.

My 2014 -2024 list.

Phinney Books, which has an exhaustive, yet engaging weekly news newsletter (a secret-gem resource for serious book lovers), has gotten its outsized share of glowing press coverage over the years; 100% earned, thanks to Tom’s bookworm curating.

This 2022 Seattle Times article by Paul Constant is my favorite, largely because Tom’s signature personality sneaks into the headline: At Phinney Books, a neighborhood bookstore has patiently assembled one of Seattle’s best browsing experiences.

It’s always a joy to head to Phinney Books around 6:30—the #5 from downtown stops right there (74th & Phinney)—as Tom quietly wraps up the day. I savor floating around the store’s bursting shelves, which lean into contemporary fiction and current events, while one of Tom’s personal, yet zeitgeist playlists spins the Feelies or Jackie Mittoo or early Fleetwood Mac. Tom, entering the day’s numbers on computer while stationed at his disheveled absent-minded-professor-nook behind the counter, inevitably looks up and makes the perfect, customized recommendation, such as his inspired pick for my City Canon syllabus: 1933’s Business as Usual, Jane Oliver and Ann Safford’s young-woman-moves-to-London send up of sexism in the city.

Though Tom’s store is relatively small, 1,200 square feet, Phinney Books’ browsing path—”True” on the north wall, “Made Up” on the south (“Cities,” “Poetry” tucked in along the way)—manages to feel akin to the 20,000 square foot circuit at Elliott Bay, a magic trick that reflects Tom’s deceptively sleepy brain waves.*

* I guess not too deceptive; he did have a star turn as a Jeopardy champion.

If you don’t live in Seattle, may I point you to Phinney Books’ Bookshop.org link.

An appropriately delightful footnote: As the event wound down, I didn’t want to call it a night. Stuck far afield in Ballard, I wasn’t sure what to do, so I started strolling into the fine evening weather south on Phinney Ridge. After walking about a mile, I landed at The Tin Hat Bar and Grill, a cozy dive in the small commercial cluster on NW 65th and 5th. Despite evidence to the contrary—lively conversations at all the tables, a line at the bar, food orders in play—I assumed last call was at hand. “How late are you open?” I asked. “Til 2 am,” the slammed, yet friendly young woman behind the bar said to my pleasant surprise.

I took the last seat at the bar, ordered a whiskey, and settled in to write. I also texted my pal Dan B., aka David Byrne; he lives a few blocks away, and since he’s always trekking to Capitol Hill to hang out with me on the Drag, I let him know I was in his neighborhood this time. He showed up about an hour later for a night cap.

2) I was reading at the spot across the street from my apartment (Monsoon) a few weeks ago when a gorgeous, lo-fi pop piano ballad came on the sound system.

The playlist at Monsoon usually goes with abstract R&B, World Music, and Jazz, so this heart wrenching bit of indie pop rock leaped out. I shazamed it, and it came up as art-hardcore rockers Fugazi. I thought, No Shazam, you are mistaken, and I shazamed it again, as did the (my age) bartender. We were both bewildered: What the hell? This is Fugazi?

I’m not a big Fugazi fan; too preachy and aggro for me, though I was appropriately awed when their first LP, 1989’s 13 Songs, came out because: 1) While I was never into hardcore, it was comforting to know that punk still had lots of battery left; 2) the athletic musicianship is startling and the catchy songwriting seems gifted from the punk rock gods above; and 3) as I’ve written before, despite having zero history as a punk rocker, I was a beatnik suburban D.C. teen during the Flex Your Head/Minor Threat/Dischord Records/anti-Reagan salad days, and I felt an affinity with all the commotion on local radio, in the City Paper, and blaring from posters around town.

Decades later, Fugazi has stunned me again: This otherworldly piano ballad is a track called “I’m So Tired” from a demos and instrumentals album they put out in 1999 called Instrument Soundtrack; it’s the soundtrack to a Jem Cohen documentary about the band. (Who knew, on all counts?)

“I’m So Tired” stars Fugazi front man (and straight edge patron saint) Ian MacKaye channeling his inner Ian Curtis in adagio gloom (think Joy Division’s “The Eternal.”)

Looking for a new song to learn on piano this week, it occurred to me that “I’m So Tired” would be a lovely tune to have in my set. I found a straight-forward youtube lesson (it’s a straight forward, four-chord song to begin with), and I’ve been lovingly settling into it all week. Along with its elementary melody, it reminds me of 1950’s “Earth Angel” doo-wop.

I have to admit, part of this minor obsession has to do with the youtube tutorial; the woman teaching the song, who has the inspiring words “create” "art” written in pen on her left and right hands, respectively, has a delightful marble-mouth lisp. When she says “two, three, four, …, C, B, G, …., A, B” it fits right in with the sedative magic of the piano ballad itself.

3) Blondie’s Eat to the Beat was the first New Wave album I ever bought; it was such a momentous occasion that I started a separate row of LPs by my K-Mart stereo, setting the New Wave records apart from the rest of my albums. (I did a similar thing with my poetry books decades later in 2017 when I flew off into my current poetry expedition.)

I came to Eat to the Beat like this: Down in the basement rec room (where my older brother’s stereo system was), the two of us disliked New Wave; we even wrote a derisive anti-New Wave song flaunting my brother’s Funk #49 ripoff electric guitar riff and my 8th grade lyrics about how the “Knack, Devo, Blondie, and Talking Heads/ were dead/ got no soul/ New Wave Music/’aint rock and roll.”

This was 1979, I was 12. And evidently, I doth protest too much, because one week later, I was all in on the new vibrations. “Accidents Never Happen,” a song by New Wave’s premiere messengers, Blondie, came on the car radio (Mom was driving). I was mesmerized by the cool clipped electric guitar and the aloof vocals. Only remembering the lyric “in a perfect world," a few weeks later at the record store (at the mall), I looked for the song on the track listings of all the Blondie albums. Eat to the Beat, their latest record, had a song called “Living in the Real World,” which I figured must be the track. I bought the record, rushed home, and eagerly dropped the needle on “Living in the Real World” (the last song on Side 2.) It didn’t sound familiar, but I convinced myself it was the song I’d heard on the radio because, in fact, it was a taut electric guitar driven New Wave banger with a soaring melody.

I can do anything at all

I'm invisible and I'm twenty feet tall

Pull the plug on your digital clock

And it all goes dark and the bodies stopHey, I'm living in a magazine

Page to page in my teenage dream

Hey, now, Mary, you can't follow me

Without a satellite, I'm on a power flight

'Cause I'm not living, I'm not living

Then, I lifted the needle and started properly at the beginning of the side.

First up, “Die Young Stay Pretty” knocked me out with it shrapnel reggae disco rhythm, a melody line in its own right playing counterpoint to the perfectly vain lead vocal.

Next up, “Slow Motion,” an upbeat cascade of catchy pop hooks.

And then “Atomic,” an obvious strobe light hit wherein Debbie Harry intones "Atomic/Your hair is beautiful/tonight,” against the radiating space age orchestration of pulsing polka bass, warbling keyboards, and alien guitars.

Song after song—the minimalist and lush twinkle of “Sound-A-Sleep,” the monster-mash punk attack of “Victor”—I couldn’t believe how good this record was turning out to be. And then the showstopping teen drama of “Living in the Real World,” again.

I flipped the LP over and listened to Side 1.

First up… Oh. I know this unstoppable pop song, “Dreaming.” It had been on the radio too. Those big beat Buddy Holly drums. Those jet plane guitar hook contrails. And, the booming plaintive melody, sung as if 21-year-old Katherine Deneuve had been transported from 1964’s teen movie musical Les Parapluies de Cherbourg to the stage at CBGB circa 1975.

Vite vite, walking a two-mile. Meet me, meet me at the turnstile

I never met him, I'll never forget him

Dream, dream, even for a little while. Dream, dream, filling up an idle hour

Fade away (woo), radiateI sit by and watch the river flow

I sit by and watch the traffic go

Next. “The Hardest Part.” More shape shifting discotheque rhythm section melodies intertwined with siren guitars. And swoon, Debbie Harry’s nitro come ons were making me woozy.

Then tracks 3 and 4, the melodramatic whoa-whoa retro ‘60s pop of “Union City Blue” and “Shayla.'“

As a kid who preferred mid-60s power pop like the Kinks and the Who and the Troggs, along with late 1960s psychedelic lyrics (much more than the contemporary hits that my junior high peers liked), I suddenly felt seen thanks to Blondie’s meta teen mag beat club jams and sci-fi poetry. (Hearing the B-52s cover Petula Clark’s 1965 hit “Downtown” later that year, I officially confirmed I was in on New Wave’s secret handshake, although I certainly had unofficial confirmation when Debbie Harry channeled the Supremes on the aforementioned “Slow Motion,” calling out “Stop!” drenched in echo to emphasize the allusion.)

Next, the joy ride rock & roll title track, “Eat to the Beat,” a nod to the band’s punk days, pizza, and masturbation.

Now it was on to the last song.

That portentous, dampened guitar intro? Wait. Those detached vocals?

So I won't believe in luck

I saw you walking in the dark

So I slipped behind your footsteps for a whileCaught you turning 'round the block

Fancy meeting in a smaller worldAfter all accidents never happen

Could have planned it all

Precognition in my ears

Accidents never happen in a perfect world

This was the song I’d heard on the radio! I was giddy. Yes, “Living in the Real World” was exciting , but “Accidents Never Happen” (written by Blondie’s keyboard player Jimmy Destri) was transcendent.

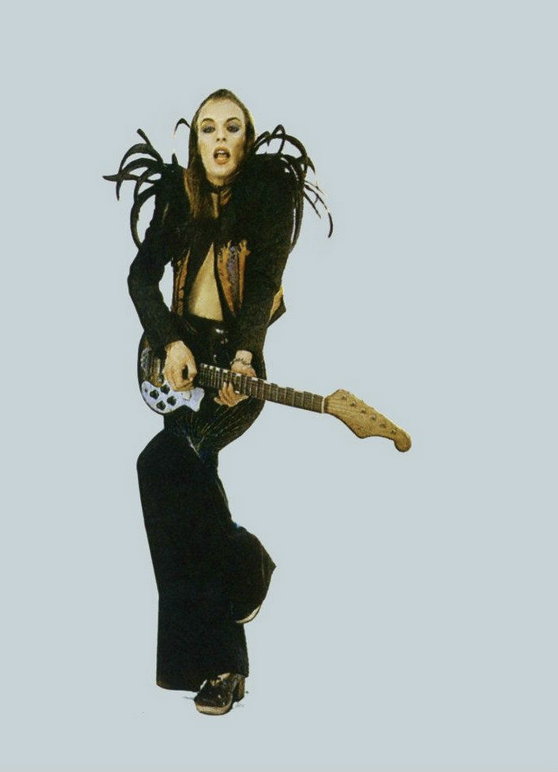

I’m currently reading the new memoir by Blondie guitarist Chris Stein, Debbie Harry’s then boyfriend, and it prompted me to revisit Eat to the Beat this week; I’ve never stopped listening to the tracks on their own over the years, but it’s been decades since I cued up the whole album.

Besides the absurd blues (?) harmonica solo (yikes) on Side 1’s otherwise wonderfully raucous title track—”Hey, you got a tummy ache and I remember/Sitting in the bathroom drinking Alka-Seltzer/Eat to the beat”—there isn’t a less-than heroic moment on this record. Combining mod mid-‘60s guitar power, disco and reggae rhythms, Giorgio Moroder synth programs, in-the-style-of Philip K. Dick lyrics, and a girl group doo-wop sensibility, Eat to the Beat is a meteor shower of music.

Cocky songwriting swagger aside, there are three common denominators to this set’s seemingly disparate CBGB versus Studio 54 impulses.

FIRST, there’s the production.

Made in 1979 with it’s eyes on the future, Eat to the Beat leaves the ‘70s behind. This is not a stoned LP. No swampy guitar distortion. No groovy funk jam session. There’s not even the transistor burn of Sex Pistols or Clash late ‘70s punk here. Nor, thankfully, does Eat to the Beat lean toward the boxy, gated production aesthetic of the 1980s when all records would sound constipated.

Each instrument on Eat to the Beat—the punchy bass, the Bay City Rollers guitars, the Mersey Beat drums, the outer space synths, and the Greta Garbo vocals—is delineated in bright relief, while collectively casting a halo.

Mike Chapman was at the control board for Eat to the Beat; he also produced 1979’s equally fine-tuned New Wave masterpiece Get the Knack by one-hit-wonder sensations, the Knack.

SECOND, the star of the this expert mix is Blondie’s drummer Clem Burke.

Every track on Eat to the Beat, from pop dynamos like “Dreaming,” to sexy disco rock like “The Hardest Part,” to insouciant pop like “Union City Blue” is driven by Burke’s rolling tympani fills and non-stop trap kit assault.

THIRD, and most important: Debbie Harry’s vocals.

Standoffish, aloof, dispassionate. All true. Whatever motivated Debbie Harry’s artistic drive, even after her 2019 tell-all memoir, remains a mystery. However, the juxtaposition of her blasé vocal style with her radiant, note-perfect arias elevate Eat to the Beat’s well-crafted pop strains into late 20th Century classics. The vocals on Blondie songs are not simply a medium for the musicianship of the band. Harry’s singing is expert musicianship in its own right. You can hear this on all Blondie records, including on the earlier ones when the production was slapdash, and the later ones when the songwriting was diminished. On Eat to the Beat, their 4th album out of 6 total from their original 1970s/80s heyday, both the production and the songwriting were blazing. Alongside Harry’s effortlessly golden voice, the meteor showers aligned.

A 1972 Bowie single; 2024 medication; and an 1851 French novel.

A magic trick on the mind.

I’m All Lost in…

the 3 things I’m obsessing over THIS week.

#36

1) Shortly after David Bowie released his 1972 glitter rock masterpiece The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, he recorded and released the devastating, barely three-minute retro rockabilly single, “John, I’m Only Dancing.”

With flip, bisexual rock god swagger backed by a triplet shuffle on Eddie Cochran acoustic guitar, and heavily distorted, snarling melodies from his spaceman cohort Mick Ronson’s electric guitar, Bowie recites his come-on lyrics in Lou Reed cant:

“I saw you watching from the stairs/you’re everyone that ever cared/oh lordy/oh lordy/ you know I/ need some loving/I’m moving/touch me.”

As summer starts this week, I’ve set out to replicate this sweltering jam on piano.

The trick lies in nailing both the long-short swing of the opening 1950s rock figure in the left hand and the corresponding, precise, yet coy sing-song melody in the right. If I can get that groove down, the rest of the song, loaded with lyrical melodies, flows from there.

The last of these melodic lines hints at the pop avant-garde by first hitting the 7th in the top of the phrase, an F# here in the key of G major, and then, playfully, a flat 7th, a plain F, in the second half of the phrase. This provides a sly set up (and noteworthy juxtaposition) as the song comes back around to the traditional rock and roll shuffle intro again.

The combo of 1970s art glam and 1950s rock and roll innocence captures the sardonic and ambivalent futurism of the waning youth counterculture of the time. It also echoes the exuberant dualities of Bowie’s lyrics.

We’ll see what I can do on solo piano.

2) After living through a batch of panic attacks—a lovely new phenomenon in my life, including waking up to paramedics one Saturday afternoon last November because I fainted in a Capitol Hill restaurant—my doctor prescribed Propranolol. “Just take one whenever you need to,” he said, writing out a prescription for automatic refills. I swallow the light green pills whenever I feel the weight of my heart welling up in my throat.

Propranolol is a beta blocker, a miracle class of meds that address the physical symptoms of panic, like a pounding heart and speeding blood pressure.

By calming your system, beta blockers simultaneously perform a magic trick on the mind: as the physical symptoms subside, your brain takes note, and your mental state of panic subsides as well. As opposed to literal anti-anxiety medications such as Alprazolam (Xanax), and Lorazepam (Ativan, the subject of an earlier I’m All Lost in… obsession), beta blockers don’t affect your mood by regulating neurotransmitters, but rather, by slowing your heart rate.

Propranolol’s irrefutable physiologic logic talked me down once again this week. I was feeling that familiar high pitch in my chest—a foreboding that turned my heart both alarm-red and depressed-blue all at once. Unable to get any work done, I took the medication and less than 15 minutes later, the miraculous effect was tangible. The beach ball in my throat was gone, and the existential blues had disappeared.

Don’t let my devoted five-star drug review scare you. I’m not turning into a fiend. I can count on one hand the number of times in the last six months I’ve turned to my scrip; in fact, at my most recent checkup last month, my doctor told me I didn’t have to be so “precious” with the prescription. (In addition to telling him how effective the drug had been, I had also reported that I use them judiciously because I don’t want the effects to diminish with frequent use; he assured me I wasn’t making any sense.)

Propranolol, however, makes perfect sense.

3) My own private city studies seminar (which last year, focused on mid-19th Century Industrial Revolution Manchester novels such as Elizbeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton and Charles Dickens’ Hard Times, and this year seems to be focusing on 21st Century Lagos novels such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah and Damilare Kuku’s Nearly All the Men in Lagos are Mad), has suddenly returned to the 1850s, though not to Manchester.

It’s Paris this time.

I’m reading Henri Murger’s 1851 Scenes of Bohemian Life. Murger’s novel (more a collection of short stories starring a recurring crew of Latin Quarter young souls in their charming, starving-artist garrets) was the source material for Puccini’s famous 1896 opera La bohème.

I’m only 10 stories in, there are 23 in the collection, and to my surprise, as opposed to more bittersweet urchin chic literature like Bertol Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, or my favorite urbanist novel, Colin MacInnes’ Absolute Beginners, this seems to be an all-out madcap comedy.

It’s as if the Marx Brothers were the main characters in 1001 Arabian Nights. The Marx Brothers in this instance being Rodolphe the poet, Marcel the painter, Schaunard the musician, and Colline the philosopher, gallivanting and stumbling their way through offhanded urban parables, constantly in need of rent (or date) money while pursuing their Quixotic masterworks, such as Marcel’s grand painting “The Passage of the Red Sea.”

A perfect example of Murger’s sit-com chaos plays out in the story “The Billows of Pactolus.” In this installment of Rodolphe, Marcel, Schaunard, and Colline’s merry poverty, named after a river from Greek mythology laced with gold ore sediment (presumably making its riches hard to grasp), Rodolphe suddenly comes into some money (500 francs!) and sets out to “practice economy” with the convoluted logic of a dreamer: the first thing he buys with his windfall is “a Turkish pipe which he had long coveted.”

""This is my design. No longer embarrassed about the material wants of life, I am going seriously to work. First of all, I renounce my vagabond existence: I shall dress like other people, set up a black coat, and go to evening parties. If you are willing to follow in my footsteps, we will continue to live together but you must adopt my program. The strictest economy will preside over our life. By proper management we have before us three months' work without any preoccupation. But we must be economical."

"My dear fellow," said Marcel, "economy is a science only practicable for rich people. You and I, therefore, are ignorant of its first elements. However, by making an outlay of six francs we can have the works of Monsieur Jean-Baptiste Say, a very distinguished economist, who will perhaps teach us how to practice the art. Hallo! You have a Turkish pipe there!"

"Yes, I bought it for twenty-five francs."

"How is that! You talk of economy, and give twenty-five francs for a pipe!"

"And this is an economy. I used to break a two-sous pipe every day, and at the end of the year that came to a great deal more."

"True, I should never have thought of that."

They heard a neighboring clock strike six.

"Let us have dinner at once," said Rodolphe. "I mean to begin from tonight. Talking of dinner, it occurs to me that we lose much valuable time every day in cooking ours; now time is money, so we must economize it. From this day we will dine out."

"Yes," said Marcel, "there is a capital restaurant twenty steps off. It's rather dear, but not far to go, so we shall gain in time what we lose in money."

"We will go there today," said Rodolphe, "but tomorrow or next day we will adopt a still more economical plan. Instead of going to the restaurant, we will hire a cook."

"No, no," put in Marcel, "we will hire a servant to be cook and everything. Just see the immense advantages which will result from it. First of all, our rooms will be always in order; he will clean our boots, go on errands, wash my brushes; I will even try and give him a taste of the fine arts, and make him grind colors. In this way, we shall save at least six hours a day."

Five minutes after, the two friends were installed in one of the little rooms of the restaurant, and continuing their schemes of economy.

"We must get an intelligent lad," said Rodolphe, "if he has a sprinkling of spelling, I will teach him to write articles, and make an editor of him."

"That will be his resource for his old age," said Marcel, adding up the bill. "Well, this is dear, rather! Fifteen francs! We used both to dine for a franc and a half."

"Yes," replied Rodolphe, "but then we dined so badly that we were obliged to sup at night. So, on the whole, it is an economy."

Needless to say, abiding by their delusional budgeting scheme, they promptly go broke. As the story concludes (and after firing their costly servant), Rodolphe muses: “Where shall we dine today?'“ and Marcel replies, “We shall know tomorrow.”

On a related note, I’m also reading (Blondie guitarist) Chris Stein’s memoir. With his glitter makeup and long hair tales of living off welfare in abandoned lofts, playing bit parts in art film flops, and doing drugs with his band scene pal, precursor punk faerie rocker Eric Emerson, Stein’s stories from early 1970s Lower East Side Manhattan overlap with Murger’s 1840s fables from the Left Bank.

With his first person account of the endlessly fascinating era when hippies were transforming into punks in NYC’s downtown art scene, Stein, who has a charming, humble and earnest online presence today, by the way, is working with rich source material (like the day in 1973 when his girlfriend Debbie Harry comes back to her Little Italy apartment from her job at a New Jersey salon with her hair dyed blond.)

Unfortunately, despite the perfect bohemian trappings, Stein writes with zero craft or reflection and the book reads as if he simply hit record and proceeded to reminisce without purpose. I have no idea, for example, why Stein loves, or even plays music in the first place. Or, for that matter, how his high school band ended up opening for the Velvet Underground.

Alas, I’m reading every word.

From 1975: “We went to some guy’s basement recording studio in Queens. Nobody had a clue where we were… It was miserably hot in the basement but we managed to get five tracks done, including a version of what would later evolve into ‘Heart of Glass.’”

Emma Cline’s short stories; Yusef Lateef’s “Eastern Sounds;” Governor Hochul’s awful decision. And a note on NBA great Jerry West, RIP.

Mysticism with shapes

I’m All Lost in …

the 3 things I’m obsessing over THIS week.

#35

1) I turned to one of my favorite contemporary novelists, Emma Cline—The Girls (2016), The Guest (2023)—to jar me out of my recent reading slump. And it worked. In this instance it was short stories, her riveting 2020 collection, Daddy.

Given that most of the 10 dark stories here play out in proximity to male violence—or the ubiquitous possibility of male violence—the title, as my book store bestie Valium Tom suggested, seems to be a Sylvia Plath reference. Otherwise, the only explicit reference to “Daddy” comes in the final story “A/S/L” (sex hookup slang for “Age, Sex, Location”) as the online handle—”DaddyXO”— of Thora, a woman who spends all her time catfishing oafish men. The listless wife of a non-descript, “not a bad person”-husband named James, Thora lies awake texting “furtively on her phone…while James slept, his back turned to her” posing as an 18-year-old high school cheerleader. The story is set, presumably after Thora crashes and burns from her phone sex addiction, in a high-end rehab facility where she then contemplates seducing a famous Me-Too’d TV chef, “G”—who has landed at the facility as well. Thora is exactly the kind of damaged soul who inhabits Cline’s fiction.

However, the majority of the stories, the best of them set in Cline’s flawless simulacrums of ennui-laden, Slouching Toward Bethlehem Southern California, feature men as the despondent central characters: a diminished abusive 60-something father who is bemused by his distant and aimless adult children during their annual holiday season visit home; a Me-Too-disgraced magazine editor now groping through a pity assignment working on a book by a wealthy tech/lifestyle guru, and then botching the rare career opportunity by aimlessly hitting on the guru’s assistant; a divorced, fading movie producer suffering through his surfer-bro son’s banal directorial debut during a tacky theater rental screening; a simmering and distant father (with an alcohol and opioid addiction) called in to rescue his troubled, violent son after the boy gets expelled from an elite private school.

And, in the collection’s showstopping story, “Arcadia” (originally published in Granta and which I actually first read in The Best American Short Stories 2017), one of the few characters here who appears to have a moral center: an earnest boyfriend/live-in farmhand navigating the fraught household of his pregnant girlfriend and her erratic and frightening older brother, who owns and runs the farm.

Like much of today’s short fiction, Cline’s stories remain mum on specifics, only hinting at the crux of the conflict at hand while preferring to linger in deceptively casual dialogue, quietly startling observations, and the minimalist realism of daily lives. The understated stories usually include a dramatic scene too, well-placed land mines that offer some sort of allegory when their explosive glare sheds light on the otherwise repressed narratives.

Cline is a master of this form, particularly pivoting to violent scenes—the impromptu dentistry in “Marion” (which struck me as an early draft of Cline’s Manson Family novel The Girls), or most notably, a terrifying porn-inspired night, drunkenly orchestrated by the dangerous aforementioned older brother in “Arcadia.”

It’s the quality of Cline’s keen observations, with their crisp verisimilitude, that make her stand out from the pack of writers working in this style of enigmatic storytelling. Whereas most writers—I’m thinking of Sally Rooney—tend to tack on observations that fall outside of the scene (I jest, but something akin to, “a crash of thunder sounded in the distance…”), Cline’s breadcrumb asides—"We sat in the back of Bobby’s pickup as he drove the gridded vineyards and released wrappers from our clenched fists like birds” … “‘Home around five,’ she said… [loosening] her hood, pulling it back to expose her hair, the tracks from her comb still visible….”—feel intrinsic to the action at hand while simultaneously commenting on it.

What also makes Cline stand out from the pack, is this: While feminist at their core, her stories are deeply sympathetic to both women and men (who she seems to have a surprisingly uncanny inside track on) as she portrays both genders as trapped in the manufactured doubts scripted by societal roles, but also born of the stultifying human condition.

(I wrote a review of Cline’s second novel, The Guest, last year, which also includes a lot of thoughts about her first book The Girls. Scroll down down down to find that review here.)

2) An Instagram account I evidently follow (or does it follow me?) posted a picture of 1950s/1960s jazz polymath Yusef Lateef’s 1962 masterpiece LP Eastern Sounds, quipping: “Long before André 3000.”

There’s no connection between New Blue Son, André 3000’s surprise 2023 experimental flute-forward art album and Lateef’s tuneful hard bop/modal jazz set except maybe the array of obscure instruments both records roll out in concert with the flutes: Sintir, mycelial electronics, and plants on 3000’s new age reverie ("The Slang Word P*ssy Rolls Off the Tongue with Far Better Ease Than the Proper Word Vagina. Do You Agree?" is my favorite track on the Outkast star’s better-than-you-think-it’s-going-to-be record) and Xun and Rubab on Lateef’s stately mix of blues, Middle Eastern, and Asian studies. (Lateef also counted the biblical-era, Jewish shofar in his musical repertoire.)

Ultimately, the funny Instagram post led me back to Lateef’s great record, which I likely haven’t listened to since I had a jazz radio show (1960s free jazz, specifically) at WOBC 37 years ago.

It turned out one listen wasn’t enough. Nor two. Nor three. I had Eastern Sounds’ refined kaleidoscope of walking blues, easy ballads, rhapsodic love themes, Asian sketches, playful melodies, and delicately crushed piano (pianist Barry Harris’ soft colors quietly define this album) playing on repeat all week.

A meticulously arranged, almost self conscious, 40-minute set of nine jams that sway between elegant, elementary, bluesy (track 2, “Blues for the Orient,” would be the single if jazz records did that), modal, cinematic, and occasional hints of John Coltrane’s free-saxophones-to-come-later-in-the-decade, Eastern Sounds distinguishes itself—even during this era of perfect jazz records—with a loving dedication to melody.

Unlike André 3000’s drone-driven experimenting, this is mysticism with shapes.

You can hear Lateef taking in breaths between the precise xun phrases on the opening tune, “The Plum Blossom,” a nursery-school-melody-meets-music-theory-seminar jam. I initially found this intimacy distracting. But like the Ornette Coleman, Thelonious Monk, and Bill Evans records from the same era, this is a rambunctious workout, despite—or perhaps because of—its meditative mission.

3) I would certainly love to join a lawsuit against New York Governor Kathy Hochul over her decision to “pause” congestion pricing; starting on June 30th, New York City was set to be the first American city to follow London, Stockholm, Milan, and Singapore where congestion pricing, a surcharge on cars entering the downtown core to help fund transit, is key to supporting sustainability. On the books for two decades, for example, London’s program has decreased greenhouse gases, increased transit use, and reduced congestion. Hochul’s bail on the program is dispiriting.

I snapped this photo on my July 2017 trip to London

I’ve been obsessed with congestion pricing for years; I even wrote an early poem about congestion pricing in 2017.

More recently, arguing that Seattle should enact a more progressive program than the Manhattan proposal, I wrote a PubliCola column calling for “sustainability pricing,” charging car commuters who drive into any of Seattle’s dense neighborhoods—not just the downtown core. Moreover, the money, I argued, wouldn’t go for transit, but for new, affordable, dense housing, and it would flow to the very neighborhoods and suburbs where the commuters were driving in from—to build density there. (The fee would go away after enough housing is built.)

The data—lower carbon emissions, decreased traffic congestion, increased funding for public transit infrastructure—doesn’t merely support implementing congestion pricing, the numbers also show that the supposed populist argument against congestion pricing (it hurts regular New Jersey folks) is inaccurate: A meager fraction, 1.5 percent, of commuters would’ve had to pay the toll. (And hey, New Jersey, as NYC’s MTA director has argued, what about those New Jersey Turnpike tolls?)

Meanwhile, about 85% of the people who come into Manhattan’s central business district—where congestion project would be implemented—take public transit anyway.

Consider this populist data: 1) While poor people (those earning less than $13,000 a year) represent only 13% of the U.S. population, they represent a disproportionate 21% of transit riders in America. 2) Lower income people ($25,000 to $49,000 a year) make up the biggest segment of transit ridership (24%). And 3) People of color, who make up about 40% of the U.S. population, make up 60% of transit ridership. Of that group, African Americans, who make up about 12% of the population, have far away the most outsized transit ridership numbers at 24%; the median Black income is about $53,000, 32% lower than whites.

Only in the Trump era could something as fundamentally populist as public mass transit be considered elitist; when I was fretting about this to ECB, she said matter-of-factly, “Well, we live in backlash times.” Governor Hochul’s retreat on congestion pricing was reportedly a cave to swing district Democrats who are scared of Trump’s anti-urban, anti-congestion pricing rhetoric.

Anti-congestion pricing populism is not a fact based position. It amounts to baseless, anti-city virtue signaling. A perfect reflection of this disingenuous posturing comes from the most outspoken critic of congestion pricing, New Jersey Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ, 5): Only 1 percent of the constituents in his district even commute into Manhattan’s central business district, the part of Manhattan that would have been subject to congestion pricing; and by the way, the median household income in Bergen County, Gottheimer’s district, is $125,000.

In a series of editorials published the week since Gov. Hocul torpedoed congestion pricing, the New York Times has certainly laid out the benefits of congestion pricing and exposed the tortured arguments against it. Here’s a particularly compelling passage:

In her announcement, Hochul emphasized the precarious state of the city’s recovery from the Covid pandemic, but car traffic into Manhattan has returned to prepandemic levels, as has New York City employment, which is now higher than ever before; New York City tourism metrics are barely behind prepandemic records and are expected to surpass them in 2025. Tax coffers have rebounded, too, to the extent that the city canceled a raft of planned budget cuts. The one obvious measure by which the city has not mounted a full pandemic comeback is subway ridership — a measure that congestion pricing would have helped and pausing it is likely to hurt.

In announcing the pause, she also expressed concern for the financial burden the $15 surcharge would impose on working New Yorkers, though the city’s working class was functionally exempted from the toll by a rebate system for those with an annual income of $60,000 or less. In a follow-up news conference, she emphasized a few conversations she’d had with diner owners, who she said expressed anxiety that their business would suffer when commuters wouldn’t drive to their establishments. But each of them was within spitting distance of Grand Central, where an overwhelming share of foot traffic — and commercial value — comes from commuters using mass transit.

My pro-congestion pricing position takes a different angle: I think dense city districts work as offsets for the environmentally unsustainable suburbs and low-slung, low-density neighborhoods, allowing most Americans to live ecologically dangerous lives without burning down the planet. By hosting job centers, entertainment districts, and dense housing, city centers balance out environmentally cavalier suburban settings where large lots and single family zones strain utility infrastructure, promote inefficient use of resources, and wed people to GHG-heavy cars; electric cars are hardly any better because they induce sprawl, which is at the root of our environmental crisis.

Suburbanites want to eat their cake and have it too; otherwise they wouldn’t care about congestion pricing. But they want to live in GHG hot zones while flocking to cities—where, thanks to the underlying zoning for mixed-use and dense housing that’s forbidden in the suburbs, there’s a concentration of businesses, Bop Streets, services, restaurants, and exciting entertainment options. City cores should be compensated for maintaining and managing density. And more importantly, for making capacious (and voracious) suburban life possible.

____

Jerry West versus Bill Russell

While it didn’t rate as an obsession this week, I do feel compelled to note NBA great Jerry West’s death. West’s all-star career from 1960 to 1974 was before my time, but when my pro-basketball fandom started in earnest as a little boy in the mid 1970s, I did quickly ID West as my favorite player thanks to his famous last-second half-court shot in the 1970 NBA finals against the New York Knicks, which I read about in the mesmerizing NBA history book I constantly checked out of the library; the book, Championship NBA by Leonard Koppett, started with George Mikan and the 1949 Minneapolis Lakers and ran up through Willis Reed, Walt Frazier and the early 1970s Knicks.

Assigned to write a biography for what may have been my first elementary school report in the third grade, I chose West as my subject. In all honesty, I was originally drawn to him because he had the same first name as my dad, but after choosing him as my favorite, I became enamored in earnest with his role as a defining point guard (he’s literally the NBA’s dribbling figure logo) , with his raw hustle (as opposed to the supernatural skills of his more famous Lakers comrade Elgin Baylor or the outright dominance his other world famous teammate, Wilt Chamberlain), and most of all with his ultimately hopeless heroics, as he led his L.A. Lakers in repeated, tragic losses to Bill Russell’s unbeatable Boston Celtics in the 1962, ‘63, ‘65, ‘66, ‘68, and 1969 NBA finals. West actually won the MVP award in those ‘69 finals despite the Lakers’ loss, the only time a player on the losing squad has done so; he averaged 37.9 points a game over the course the 7-game series.

During West’s last few seasons, it was the New York Knicks who repeatedly beat his Lakers in the finals (in 1970 and 1973), though West finally won his only championship, out of 9 tries, in L.A.’s 1972 initial re-match with New York, the same year his Lakers won a then-record 69 games during the regular season. (Micheal Jordan’s 1996 Chicago Bulls and Steph Curry’s 2016 Golden State Warriors won 72 and 73 regular season games, respectively). The 1972 Lakers’ record 33 straight regular season wins still stands.

Oddly, while I often tear up about basketball heroes from childhood—including players from Jerry West’s era like Russell, Reed, and Milwaukee Bucks-era Lew Alcindor/Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, that I’d read about in that important book, or players from my own years as contemporary fan such as the Big E or Doctor J—I didn’t mist up about West’s death.

My own great Jerry, my dad, died earlier this year, and I cried my eyes out; it was enough tears for the two of them combined, I suppose.

Still working on my piano version of “Police & Thieves;” still checking the scores at Roland Garros; and Biden still doesn’t get it on Israel.

Whose actual nemesis is the stars…

I’m All Lost in…

the 3 things I’m obsessing over THIS week.

Week #34

1) Like time-lapsed footage of the sun moving east to west across the sky, I’ve watched my piano rendition of Junior Murvin’s reggae classic Police & Thieves transition from honoring Mervin’s mellow-mood arrangement to now mimicking the Clash’s cranked up cover version.

The shift from insouciant Kingston to insistent London started late last year when I realized the song’s hook was certainly Clash bassist Paul Simonon’s syncopated line. Before incorporating his bass-line-as-dance-number into my left hand, I’d been nonchalantly tapping the root G and A notes under the right hand melody; or in a slight nod to the Clash, I’d been playing G to A as if they were heavy barre chords on the off beat in the left hand (mimicking Clash guitarist Joe Strummer).

However, once I started bringing Simonon’s bass line—a melody in its own right— into the mix, the song went in a new direction. I started playing the slashing electric Joe Strummer chords in the right hand as accompaniment to the lyrical bass.

The Clash, 1976, L-R: Paul Simonon, Joe Strummer, and Mick Jones.

Simonon’s stop-and-start line is tricky to coordinate with the right hand—even against a rock steady reggae beat. This week, I was obsessed with embedding the groovy action into my muscle memory, gleefully practicing Joe Strummer with one hand and Simonon with the other.

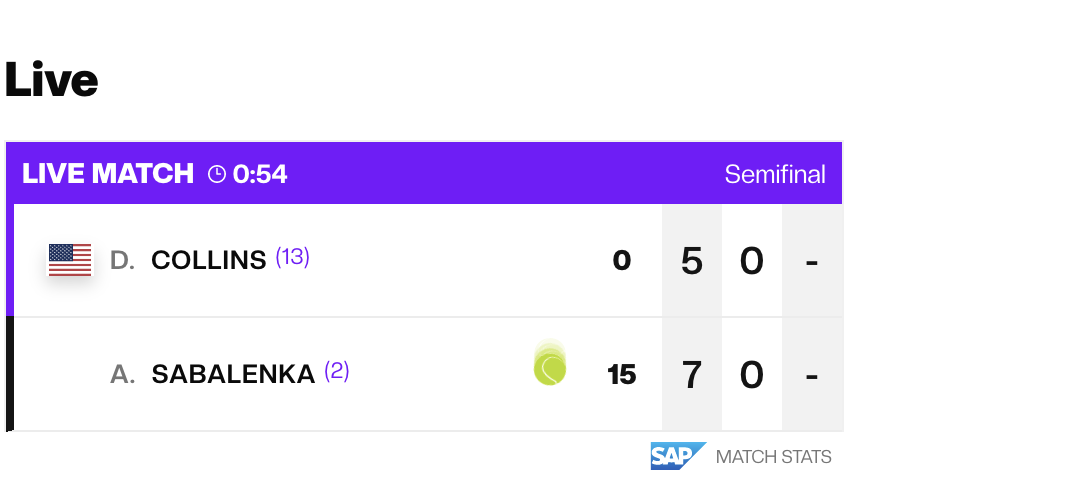

2) As I was last week, I’m still obsessed with the French Open at Roland Garros. I’m sad to say, however, that my favorite player, WTA World No. 2 Aryna Sabalenka, lost her quarterfinal match against Russian teen upstart Mirra Andreeva, who then lost her semifinal match to No. 12 Jasmine Paolini. And no one’s going to beat No. 1 Iga Swiatek anyway, who beat No. 3 Coco Gauff in their semifinal.

Count me as now hopelessly rooting for Paolini against Swiatek in the finals match.

Paris is 9 hours ahead of Seattle, so all week, I could just wake up to the results on the WTA website without having to suffer through the anxiety of watching the score ticker (and bouncing tennis ball icon) in real time. I don’t have the tennis channel, and Roland Garros is not available on Hulu or ESPN, so I haven’t been able to actually watch any of the matches.

Sabelenka wins big in the 4th Round, but she was still doomed.

Unfortunately, after a week of good news mornings (Sabalenka was sailing through the tournament, including totaling media favorite Emma Navarro 6-2, 6-3 in the sweet 16 round), her quarterfinal match on Wednesday turned out to be later in the day and suffer I did as the troubling numbers showed her eking out the first set 7-6 (7-5) and then steadily falling behind, losing the next two sets 4-6, 4-6. (Apparently, she was sick…?)

And, classic Peter Parker syndrome: Sabalenka also lost her World No. 2 status, falling behind Gauff in points in the inexorable storyline that’s at the root of my Sabalenka partisanship. I’m drawn to doomed heroes whose actual nemesis is the stars. Ever since Sabalenka’s brief ascension to the No. 1 spot was besmirched by simultaneously losing the U.S. Open to Gauff in 2023, I knew she was my kind of jinxed hero.

I wanted to think Paolini’s upset quarterfinal win over No. 4 Elena Rybakina slightly normalized 17-year-old Andreeva’s surprise win over poor, crash-and-burn Sabalenka. A day of upsets! But it’s hard to diminish the fanfare that comes with a teenaged tennis prodigy story, which put Sabalenka’s downfall— as a toppled menace—front and center.

3) Ever since Hamas fully embraced its psychotic ideology on October 7, events have unfolded in Gaza as predictably as the plot to a sophomoric apocalypse movie: Israel matched the bloodshed with their own unhinged militarism—exactly what Hamas wanted—and here we are in a spiral of devastation and hopelessness.

Equally see-through was Biden’s attempt this week to hang on to his cloying pro-Israel narrative that frames Hamas as the exclusive bad actor. Blatantly trying to set up Hamas up for a news cycle fail he proposed a ceasefire saying:

“This is truly a decisive moment. Israel has made their proposal. Hamas says it wants a cease-fire. This deal is an opportunity to prove whether they really mean it.”

But less than 24 hours later, his framing was exposed as a delusion when Israel quickly shit on his initiative:

“Israel’s conditions for ending the war have not changed: the destruction of Hamas’s military and governing capabilities, the freeing of all hostages and ensuring that Gaza no longer poses a threat to Israel,” Mr. Netanyahu’s office said in the statement released on Saturday morning.

I don’t know how much clearer Israel can make it to President Biden that they are no longer the peace-seeking nation of his imagination. * [I added this link to this line later because NYT writer Thomas Friedman wrote a column making a similar point.]

I doubt my emails get through, but I have been obsessively hitting reply to every Biden fundraising pitch I’ve gotten this week with the same response:

Josh Feit <josh@publicola.com>

Wed, Jun 5, 4:05 PM

to Biden

It is revealing that last week President Biden issued a demand on Hamas to accept a U.S./Israeli ceasefire offer, and then it was Israel who rejected it. How many times is the Netanyahu government going to embarrass President Biden before he gets the message that he needs to stop supporting Netanyahu's war?

Disappointed.

I'm not contributing until Biden changes course.

a GEN X Jew

Biden’s boy-who-cried-wolf attempts to get tough with Israel are equally credulous. He made news this week by saying Netanyahu was prolonging the war to stay in power, referring to the weighty role Israel’s jingoistic far right plays in Netanyahu’s tenuous governing coalition. Okay. Sure. But this faux cynical analysis covers up Netanyahu’s actual (not very secret) position. He’s prolonging the war because he’s 100% aligned with the extremists in his coalition. Netanyahu is not cunningly appeasing the expansionist settler zealots in his government. He himself is a zealot, and has no interest in a two-state solution.

I want to see Hamas ousted, but this war is installing violence and bloodshed as the only language of the region. In the long run, that constitutes a victory for Hamas. If it hasn’t already.

The Penguins’ “Earth Angel;” Sylvia Plath’s violent poetry; Roland Garros

As Donald Trump runs for president on a platform of mob violence.

I’m All Lost in…

the 3 things I’m obsessing over THIS week.

#33

1) Practicing “Earth Angel” on piano.

The Penguins’ single Earth Angel defines 1950s doo-wop, a genre that itself defines early rock and roll. With its melancholy time signatures, heavenly vocals, sparse arrangements, and lovesick angst front and center, doo-wop’s teen-aged arias are pitch perfect artifacts of mid-20th century America.

Earth Angel was recorded and released in 1954 during doo-wop’s showstopping initial wave when its aching pop cadences suddenly turned young vocalists into street corner composers across American cities nationwide. The result: a rush of low-budget, unbridled lo-fi singles from local DIY ecosystems made up of aspiring high school acts, rhythm-and-blues record shops, radio stations, and hustling post-War indie labels.

In the case of Earth Angel, L.A.-based gospel label Dootone (an African American-owned label) hastily put out the acetate demo featuring just vocals, piano, and bass that a crew of Fremont High students calling themselves the Penguins (after the Kool cigarettes logo) recorded in a garage.

In addition to L.A.’s Penguins, the 1953/54 class of doo-wop pioneers included (my favorite doo-wop act) NYC’s the Crows, whose 1954 smash Gee (the first doo-wop song to break the million-seller milestone) is often cited as the first rock & roll hit. What’s indisputable is that it was the first R&B chart topping record to “crossover” to the upper echelons of the Pop (read, “white”) chart.

(I wrote about doo-wop and Earth Angel at length in my 2021 essay, “Absolute Beginner Blues.”)

The Penguins’ reel-to-reel garage demo of Earth Angel (pressed straight to single and eventually climbing six notches higher than the Crows’ crossover hit) is forever marked by its DIY trappings: the opening bars were inadvertently lopped off. As a result, the song begins mid-piano intro. This historic accident may explain Earth Angel’s mysterious rhythm, which I can only describe as having an undertow. Rather than prompting a sense of resolve and ascension that pop chord patterns create by landing on the root 1 note of the key (as Earth Angel does with its standard I vi ii V/ I vi ii V/ I … “50s progression”), it nonetheless feels as if its always faltering toward resolve, rather than ascending toward resolve. Earth Angel is constantly making an attempt to begin; appropriate, perhaps, given how the recording SNAFU creates the sensation that Earth Angel never actually starts in the first place.

The only other bit of music I can think of that naturally flows-in-reverse like this, as if it’s actually moving backwards, is the beautiful spooky climax of Claude Debussy’s 1893 String Quartet in G Minor.

My attempt to replicate Earth Angel’s counterclock throughline has been the task of the week, a frustrating and euphoric one.

Fittingly, I tired reverse logic by playing the progression with a propulsive one-TWO rock back-beat. That approach, among other tricks (such as locking in doo-wop’s standard left-hand arpeggios in the style of another doo-wop masterpiece, In the Still of the Nite) did not work. The backbeat ploy, for example, simply turned the Penguins’ dreamy prayer into a polka.

Guess I’ll just have to go back to the drawing board on this song and start over.

2) Close reading Sylvia Plath’s Ariel

Trying to sharpen the life or death skill of interpreting poetry, I took my copy of Sylvia Plath’s posthumous (and Pulitzer Prize winning) collection, 1965’s Ariel, off the shelf and started reading it this week as if it was a homework exercise: I studied her verse line by line, consulted secondary sources, and then re-read the poems as if I was memorizing them.

My Friday-Saturday-Sunday night Memorial Day weekend plans? Hanging out at the bar with a whiskey and a pen marking up Sylvia Plath.

What did I find in Plath’s poems? Violence.

It’s an odd match, poetry and violence. But that’s what’s happening on the pages of Ariel.

Kamikazes, knives, vengeance, homicide, armies, poison, the Holocaust, animal traps, drowning cats (and I’m only 20 poems into this 40-poem collection.) There’s even a poem titled “Thalidomide” about the infamous drug that doctors widely prescribed to pregnant women during the late 1950s and early 1960s that caused birth deformities. Another poem here, “Cut,” turns a mundane kitchen scene into a bloody, chopping board incident. This is violence against women in particular—in natal care, in the kitchen—as Plath crafts allegories publicizing the urgent themes of the oppressive domestic scene. Plath’s Ariel reads like verse to the prose of Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique.

The excellent title poem—named, in part, after Shakespeare’s Ariel, the Tempest’s magical sky spirit trapped in servitude under magician Prospero—contemplates the ultimate act of violence, suicide. Specifically, “Ariel” is about the self-destruction inherent in the pursuit of liberation. It ends:

“And I/Am the arrow,/The dew that flies/Suicidal, at one with the drive/Into the red/Eye, the cauldron of morning.”

But apparently there is a joy in being “Suicidal, at one with the drive,”—a least when the destination is a “cauldron,” witchcraft’s means of rebirth. Along this “drive” (a horse ride through the English countryside), the narrator unites with her passions. Casting off “dead stringencies,” she is the women’s rights Paul Revere, Lady “White Godiva” on her rebel ride. Eating “sweet” berries, she savors the natural world around her. And then, Becoming one with nature itself, she transforms herself into basic physiological and geo functions: “And now I/Foam to wheat/ a glitter of seas.”

At one point she even becomes the horse. Using the Hebrew definition of Ariel, God’s Lion—though, with Plath at the reins, it’s “Lioness”—she writes:

God’s Lioness,/How one we grow./ Pivot of heels and knees!”

All this joy galloping on the way to corporeal evaporation, like the “dew that flies,” evaporating as the morning sun rises in the sky.

Plath strikes a similar ecstatic pose in “Cut.” It begins: “What a thrill—/My thumb instead of an onion/The top quite gone…” Three stanzas later, Plath is openly giddy about her own dismemberment: “Straight from the heart./I step on it,/ Clutching my bottle of pink fizz/ A celebration, this is.”

Plath’s poetry, inventive, erudite, and elegantly unruly as it is, has always struck me as a finite heirloom of the early 1960s Feminine Mystique-era. But as Donald Trump runs for president on a platform of mob violence, and as Israeli and Russian bombs devastate Gaza and Ukraine, respectively (with bloodshed looming in Haiti), reading Plath’s grisly poetry at a bar on Saturday night in 2024 felt—as great poetry always should—like a zeitgeist move.

3) The French Open at Roland Garros

I’d never heard the tennis metonym Roland Garros before until earlier this year when I watched Jay Caspian Kang’s documentary about Michael Chang’s historic win at the 1989 French Open, aka, “Roland Garros.”

This week, as the 2024 French Open got underway with headlines about former star, Japan’s Naomi Osaka’s surprise three-set near-win against current Women’s No. 1, Poland’s Iga Swiatek, and veteran Rafael Nadal’s poignant first round farewell(?) loss, “Roland Garros!” has been my favorite phrase. I exclaim it whenever the mood strikes.

Once again, for me, it’s all about following the chaotic travails of my favorite tennis player, the WTA’s No. 2, Belarusian Aryna Sabalenka, as she angles for a re-match of her Italian Open finals loss in mid May to Swiatek (and her Madrid Open finals loss to Swiatek two weeks before that.)

While it may sound like Sabalenka is in some sort of Federer–Nadal-level rivalry with Swiatek, that’s not the case. Swiatek, who easily beat Sabalenka 6-2, 6-3 in the Italian Open, holds an 8-3 advantage over Sabalenka overall (Sabalenka’s three wins over Swiatek have all taken three sets, while only two of Swiatek’s eight wins over Sabalenka have taken a three-set effort.)

While Swiatek hovers above the women’s circuit, Sabalenka is battling it out at the top of the rankings a notch below the Polish star, against peers like No. 3, American Coco Gauff (who has a more comprehensive game than slugger Sabalenka and is quietly making quick work of the competition this week) and No. 4, Kazakhstan’s Elena Rybakina, who has cruised through this week so far onto the current 4th round where she’s on a collision course with Sabalenka before either can make it to the Roland Garros finals. Rybakina won her 3rd round match against the No. 25 in two quick sets, 6-4, 6-3.

Sabalenka, who, I’ll admit, is doing better than usual (and who has, surprising us all, added a new drop shot to her game) had a more nerve racking third round showdown. Her tour circuit best friend, the former No. 3, Paula Badosa, now un-ranked, pushed Sabalenka to 7-5, 6-1.

Devil Ivy clipping start; Cape Floral NA cocktail; Impossible “chicken” sandwich.

My own private Journey Through "The Secret Life of Plants."

I’m All Lost in…

the 3 things I’m obsessing over THIS week.

#32

1) Late last year, I made some clippings from a Devil Ivy plant—snip the stem on an angle just below a node—and I put them in a small jar of water (make sure the water line is above the nodes).

Six months later, the ivy leaves were flourishing, and tails of curling white roots were crushing up against the glass. Seizing the day, I freed up a planting pot for the burgeoning Devil Ivy start by re-potting a surprisingly successful Trader Joe’s Philodendron into a bigger pot, and then, with a fresh helping of damp soil, I transferred the Devil Ivy start to the pot the Philodendron had outgrown.

This game of musical plants has embedded me in my own private Journey Through "The Secret Life of Plants" or whatever hippie Stevie Wonder world I’m in as I lovingly put my newly-potted start on the poetry bookcase by the window.

I used a Delroy Wilson, the Cool Operator LP as a trellis for the two leafy stems to bless this Devil Ivy dub project.

Newly potted Devil Ivy start (center).

On a related note, last December, my weekly list of obsessions included “Saving the Dragon Tree Plant” that my friend/ex Diana handed off.

I’m happy to report, it’s back from the dead.

2) I haven’t had any alcohol in more than a week.

Who knows how long this mini-health kick will last, but it’s been an easy pleasure thanks to the Abstinence brand bottle of Cape Floral “premium distilled non-alcoholic spirit” I bought; $50 at the overpriced bodega on my block, but $35 if you order it online from the company.

I keep checking the ingredients for cannabis because after mixing a pour of Cape Floral with soda water and lime every evening, I’ve been turning pleasantly invisible and falling right asleep.

No drugs involved, evidently. The ingredients listed are: Cape Rose geranium, juniper berries, angelica root, and coriander. Maybe it’s the angelica root, which is used in traditional European medicine to help ease anxiety.

The South African-based company claims their NA spirits are “inspired by the diverse botanicals of South Africa's Cape Floral Kingdom - the world's smallest yet most diverse floral kingdom.” Other Abstinence Brand choices include: Cape Citrus, Cape Spice, Epilogue X (“dark toasted malt … with spice botanicals and South African Honeybush, perfect for a non-alcoholic old-fashioned”), and lemon or blood orange spritz mixers.

According to one happy online review from “Laurie H. in Baltimore,” Cape Floral tastes lovely with some cranberry simple syrup, lavender bitters and sparkling hibiscus water.

I will test that soon enough, but for now I can already say highly and drowsily recommended with just soda water and lime.

3) Another recommendation from the (new) world (order) of witchcraft food and drink: Impossible brand’s “chicken” patties.

Definitely better for the environment (thanks to the softer carbon footprint than corporate chicken farming) and debatably better for you (more nutrients, such as fiber, than a chicken patty), these golden-browned patties are a tasty vegan/veggie option.

I fry them up in a pan with some virgin olive oil and plate them as the protein centerpiece in a salad sandwich—a pile of greens, fried onions, and sliced tomato, with a heavy dose of nutritional yeast.

I added red cabbage and Trader Joe’s sesame salad dressing to the mix one day this week to mimic a more classic fried chicken slider.

Pussy Riot retrospective at the Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver; a sourdough sandwich shop on Commercial Drive in Vancouver proper; and Sabalenka vs Swiatek at the WTA Italian Open in Rome.

We told them we were drama students.

I’m All Lost in…

The 3 things I’m obsessing over THIS week (Vancouver, B.C. edition)

Week #31

1) I visited Vancouver, B.C. this past weekend. My friend Wendy’s Stealing Clothes, aka, Annie, had tickets to a nostalgic (for her) rock show and a groovy Airbnb. She invited me along; not for her rock show, but for the opportunity to recline in Vancouver: lazy, grand & sparkling Stanley Park; the four-minute-headways SkyTrain (with doner kebab shops built into station platforms); the majority-minority diversity (versus Seattle’s near-70% white), and the people’s SeaBus.

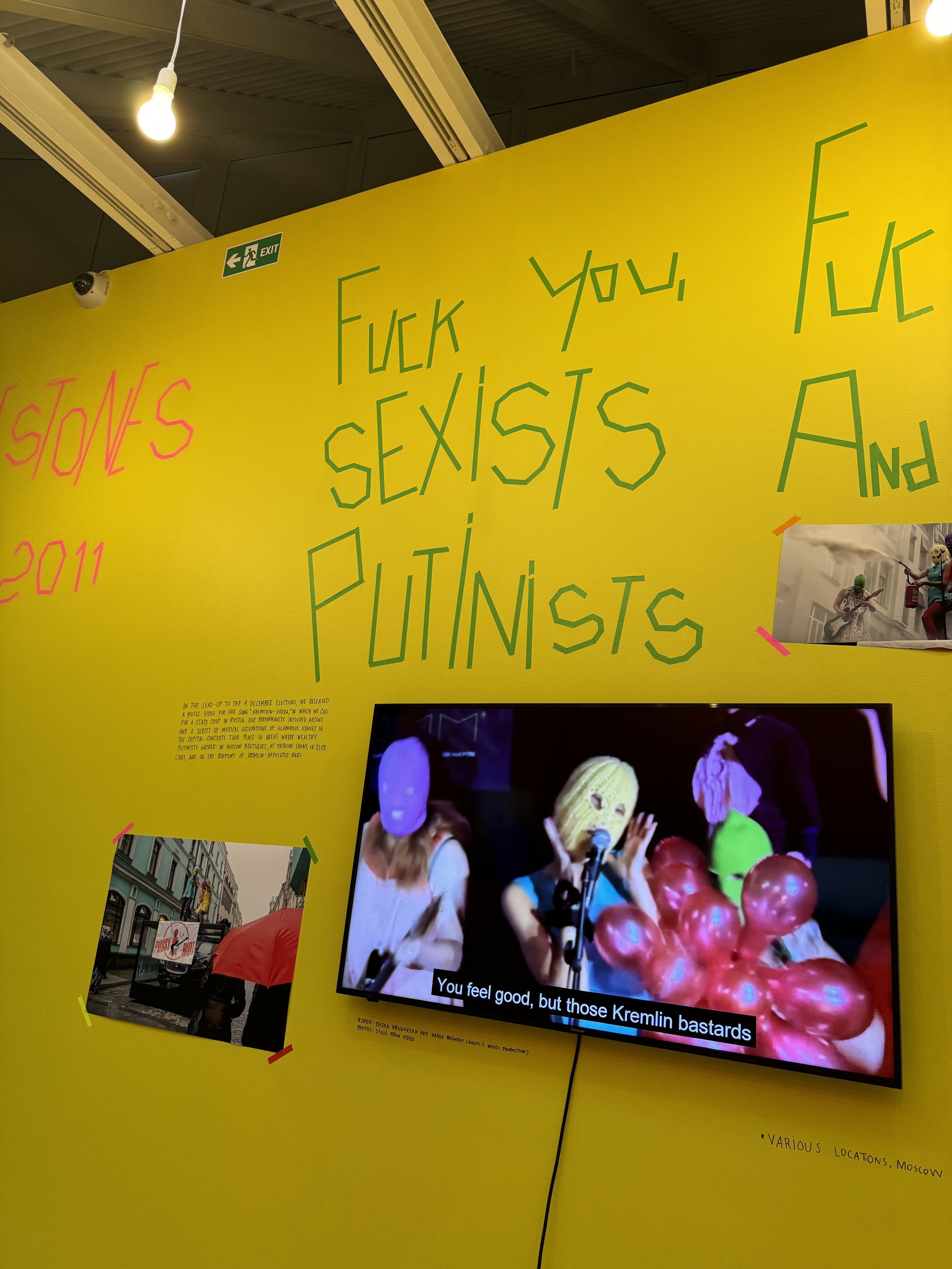

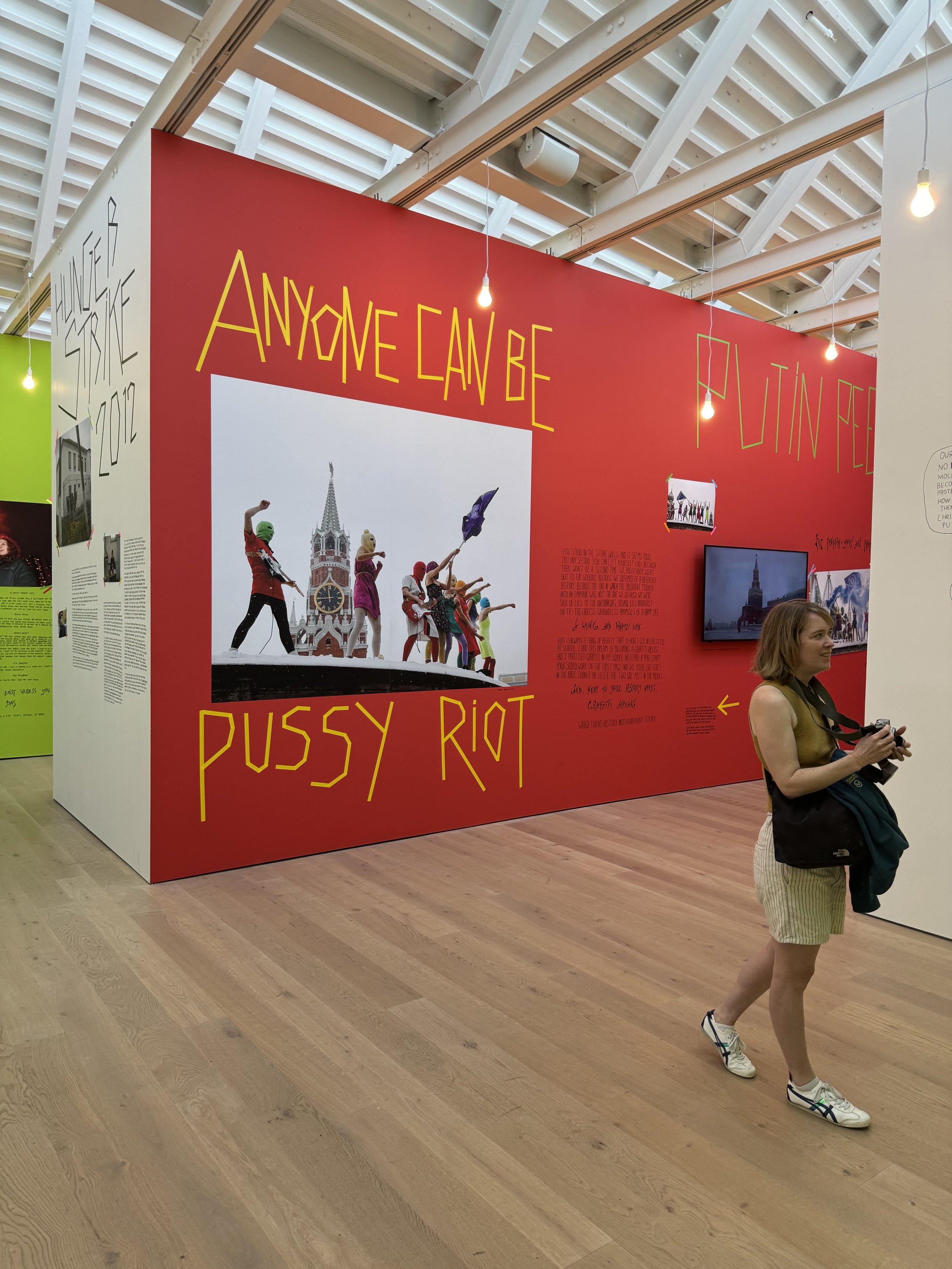

On Sunday morning, we took the SkyStrain five stops to the Waterfront Station and transferred to the SeaBus (the ferry), taking it 10+ minutes across the Vancouver Harbor to the Polygon Gallery (free admission, but $15 recommended) where we saw a remarkable exhibit: Velvet Terrorism—Pussy Riot’s Russia. This was a chronological, hedge-maze-walk-through retrospective of the anti-Putin, anti-war, anti-police state, feminist collective’s obstinate catalog of punk agitprop. Appropriately, their Riot Grrrl-inspired jams blare from video monitors as you take in the show; the person at the front desk warns you about this: “It’s loud,” she said.

Pussy Riot grabbed the world’s attention when they grabbed Russia by the balls in February 2012 after staging a guerilla gig at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savoir dressed in simple frocks, colored tights, combat boots, and knit stocking caps pulled over their heads (circle cut outs for the eyes and mouth), performing a manic song called “Punk Prayer”

Virgin Mary, Mother of God, banish Putin

Banish Putin, Banish Putin!

Congregations genuflect

Black robes brag, golden epaulettes

Freedom's phantom's gone to heaven

Gay Pride's chained and in detention

The head of the KGB, their chief saint

Leads protesters to prison under escort

Don't upset His Saintship, ladies

Stick to making love and babies

Shit, shit, holy shit!

Shit, shit, holy shit!

Virgin Mary, Mother of God

Become a feminist, we pray thee

Become a feminist, we pray theeBless our festering bastard-boss

Let black cars parade the Cross

The Missionary's in class for cash

Meet him there, and pay his stashPatriarch Gundyaev believes in Putin

Better believe in God, you vermin!

Fight for rights, forget the rite –

Join our protest, Holy Virgin

Virgin Mary, Mother of God, banish Putin, banish Putin

Virgin Mary, Mother of God, we pray thee, banish him!

Two of the members, Nadya Tolokonnikova and Masha Alyokhina got two-year prison terms after being charged with "hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.”

Pussy Riot’s aesthetic is located somewhere between the spat-out punk of Bikini Kill (though, late-50s-something-me hears the Slits), Charlie Chaplin slapstick, and Alexander Dubček’s popular 1968 Prague Spring revolution, Czechoslovakia’s original Velvet Revolution.

No disrespect to Western punk, but Antifa is real in Russia; when Pussy Riot uses the word “Gulag,” as they did in a series of theatrical protest actions in 2018 and 2019, it’s not a metaphor.

Pussy Riot—originally 11 women, including 22-year-old founder Tolokonnikova—frames things in the 1968 context from the start: their first action, in November 2011, featured their song “Free the Cobblestones,” an echo of the Paris ‘68 student protests slogan: “Sous les pavés, la plage!” Under the cobblestones, the beach!

This electric guitar banger, which also samples a 1977 U.K. punk song by the Angelic Upstarts called “Police Oppression,” urges citizens to throw cobblestones at police during election day protests; the cobblestones represented a crooked, election-year public works project kickback, and Pussy Riot performed the song atop a scaffold in a Moscow subway station while tearing pillows and raining feathers in analogy down (as opposed to actual cobblestones) on the crowd below.

Although my ‘68 comparison casts Pussy Riot as more praxis than punk, it’s hard not to conclude, after walking through this exhaustive (and exhausting) exhibit of high-brow-pranksterism, that Pussy Riot’s real jam is ultimately artistic.

Pussy Riot exhibit at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery, 5/12/24

Pussy Riot exhibit at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery, 5/12/24

This is meant as high praise. Pussy Riot, now a lose cohort of about 25 woman, most living in exile, is made up of art geniuses—irrepressible creative souls who found themselves trapped in Putin-land. The inexorable result: their oozing creativity manifests as politics.

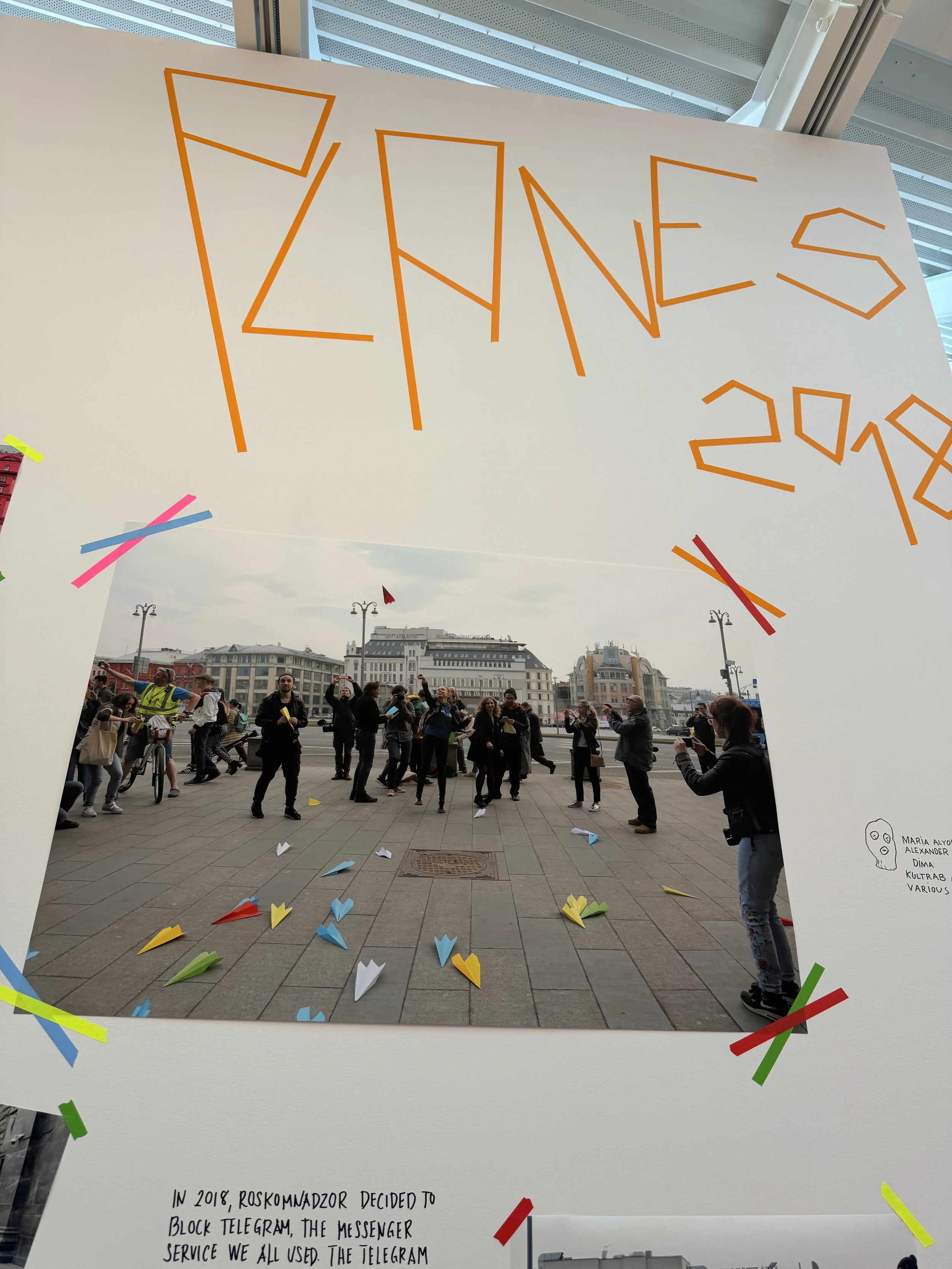

Constantly facing house arrest and arrest arrest, they persist at a level Elizabeth Warren couldn’t comprehend. But viewed as a whole body of work here, particularly as they focus on high-production videos (shot in forests and sampling Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake), theatrical costumes (such as reclaimed Kokoshniks and comedic police uniforms), colorful paper airplanes (in a protest that seemed prompted by Yoko Ono’s instruction poetry), elaborate hi-jinks escapes (using food delivery guy outfits and decoy suitcases), and songs that re-contextualize fragments of disillusioned letters from the Ukrainian front (“Mom, there are no Nazis here, don’t watch TV”), it’s plain Pussy Riot is a voltaic arts movement.

In 2018, when they plastered the federal penitentiary building with oversized stickers saying: “gulag,” “murders,” “torture,” “slave labour,” a government employee came out and told them they needed to submit all complaints in writing. Alyokhina replied: “that’s exactly what we’re doing, we just enlarged the words so that they would be readable.”

This is a mission statement. Communicating is their mission.

Also in 2018, when the government shut down Telegram, the messenger service that anti-Putin activists used to communicate, members of Pussy Riot showed up at the FSB building (today’s KGB building) and attacked it with paper airplanes; Telegram’s logo is an airplane.

Pussy Riot exhibit at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery, 5/12/24

Pussy Riot exhibit at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery, 5/12/24, Masha Alyokhina pictured with blue paper airplane.

Pussy Riot exhibit at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery, 5/12/24

The text that narrates the exhibit was written by one of the collective’s original members, the poetic Alyokhina, which makes it hard to miss the fact that artistic genius governs Pussy Riot’s overt politics. Juxtaposed against the kidnap letter sloganeering splayed on the gallery walls in green, orange, and yellow masking tape (“Fuck you, SEXisTs, PuTiNists,”), Alyokhina writes the exhibit’s narrative in effortless metaphors

“You can be imprisoned for talking to friends about politics at McDonald’s. For two years I have seen [the prison system] from the inside. It is a meat grinder…”

and default prose poems.

Riot is always a thing of beauty. That is how I got interested. At school, I had this dream of becoming a graffiti artist, and I practiced graffiti in my school notepad. If you start your schoolwork on the first page and do your sketches in the back, sooner or later the two will meet in the middle.

Next to your history notes, graffiti appears. Which turns history into a different story.

If Alyokhina’s magical verse isn’t enough to signal Pussy Riot’s status as high art, her report on Pussy Riot’s 2012 Red Square performance of “Putin Peed his Pants” from atop the historic Lobnoye Mesto altar explicitly spells out the nature of their project:

“The cops got us afterwards for trespassing. We told them we were drama students.”

Doner kebab shop built into the SkyTrain platform, Vancouver, B.C., 5/11/24.

2) Another dispatch from Vancouver—specifically from Commercial Drive, the main drag east of downtown that stretches through the lively yet insouciant Grandview-Woodland neighborhood where the closely packed detached houses lining the side streets translate into a density rate (17,000 people/per square mile) that tops the city average by 3,000 people per square mile.

Trout Lake Park, Vancouver, B.C.

Vegan pizza on the drag, Vancouver, B.C., 5/13/24

Commercial Drive is a two-miles-of-action strip (and notably multi-generational as opposed to teeny bopper heavy) defined by: lefty, used bookstores; secondhand clothing and consignment shops; cafes; an abundance of pizza slice joints (including the Pizza Castle for plant based vegan slices); tattoo parlors; coffee shops; Caribbean, Asian, Mexican, and Roti restaurants (vegan options everywhere); and (too many) sports bars.

It’s bordered on the south by a major SkyTrain stop (the third busiest station in the three-line SkyTrain system, the Broadway/Commercial Station, with roughly 15,000 daily boardings); bordered on the southeast by a gorgeous wooded lake beach (Trout Lake Park); and bordered on the north by a hippie park (Grandview Park).

Out of all the action, the coziest spot to sit down for a glass of red wine or a cocktail is located directly across the street from Grandview Park, a slow-paced hang out called Mum’s the Word. We landed there twice.

First for drinks. I got—per the “or just ask for what you like!” drink-menu option, a custom made NA cocktail. Annie got a “Them Apples”— butter washed Pere Magloire V.S., Merridale apple liqueur, maple syrup, egg white, black walnut bitters, and lemon.

The next night, for dinner. I got the “Hippie Mum”—fried eggplant, tomato sauce, herbs, vegan shredded cheese, served on sourdough.

I don’t know what Annie got, but the comfort food menu includes a long list of grilled sourdough sandwiches: Melted Swiss cheese with onion jam; a field roast vegan sandwich with spicy vegannaise and caramelized onions; a beef patty melt; a BLT; a meatball sub; a smoked turkey with chimichurri; a Gruyere cheese and country ham sandwich; and a “Korean Mum”—Bulgogi marinated smoked beef, kimchi, mozzarella, and mayo.

We sat on the back deck for both visits (for the view of the park), but there’s also low-key indoor lounge that may as well be in Portland with a DJ spinning casual beats and a struggling artist bartender chatting with the regulars.

The New York Times’ “36 Hours in Vancouver,” also highlighted Mum’s the Word, writing: “equal parts cafe and cocktail bar—locals slip into retro easy chairs for drinks like Mum’s Cold Brew Manhattan (14.75 dollars), a potent mix of cold brew, whisky and kahlua.”

The next time I visit Vancouver, I will go straight back to Mum’s the Word.

I’ll also go back to Prado Cafe—one of the 20 coffee shops on Commercial Drive—and the other place I hit twice during this weekend trip, both times for their whopping quinoa and arugula bowl.

Final note: There’s a Kitchener St. in the heart of the Commercial Drive drag; given that there are at least two world music record shops and a Jamaican restaurant called Riddim & Spice nearby, one couldn’t be blamed for thinking this street was named after Windrush Generation Trinidadian London transplant, 1950s Calypso icon Lord Kitchener.

“Isn’t that your guy?” Annie said. (She said the same thing about the President Gamal Nasser LP of speeches we saw!) Kitchener street was established in 1911, so I guess not, but it seems to me that just as Calypsonian, Aldwyn Roberts, aka, Lord Kitch, was sampling and reclaiming the early 20th Century British mustachioed military leader, the pro-immigrant Commercial Drive neighborhood has transformed meanings as well.

SkyTrain, Expo Line, Vancouver, B.C., 5/13/24

3) And now we leave Vancouver, B.C. for Rome. Or at least, for my current obsession with what’s been happening in Rome: Pro tennis’ Italian Open.

To be honest, I’m only paying attention to the women’s side, the WTA, and my favorite player, Aryna Sabalenka, who, in her inimitable, discombobulated style (including faux pas-ing and laughing her way through a sit down interview, and nearly botching her Round-16, 3-set epic by barely fending off three match points) now finds herself in the finals.

Sabalenka (ranked No. 2 in the world) will be facing Iga Swiatek (No. 1 in the world) for the championship on Saturday.

Per usual, Swiatek blazed her way into the finals, handily dispatching all her opponents, including world No. 3 Coco Gauff in the semifinal in two sets. Swiatek also beat Sabalenka last month in the Madrid Open final, 7-5, 4-6, 7-6 (7). And Swiatek holds a 7-3 advantage overall against Sabalenka.

The WTA’s Aryna Sabalenka, ranked No. 2 in the world.

I’m not being 100% fair to Sabalenka; to my glee and amazement, she seems to be in a bad rhythm of her own now. After her close call in Round 16, she went on to win her quarterfinal match against Jelena Ostepenko (the No. 9) in two sets, 6-2, 6-4, and win her semifinal against the streaking Danielle Collins (No. 13), 7-5, 6-2.

Obsessively checking the scores all week has also nudged me back onto the tennis court myself where I pretend I’m Sabalenka as I bash and volley with the practice wall—and when there’s no one else around—cry out: “Sabalenka Afternoon!”

Whatever Became of Mahmoud Hassan Pasha?

Near-by, …thereby

One of my poems, “Evelyn McHale Chooses the Tallest Building in the City,” an epic at five pages, includes a brief section about Mahmoud Hassan Pasha, the Egyptian delegate to the U.N. during 1947’s now hyper-topical special session on the Partition of Palestine.

To date, working on that poem is the closest I’ve come to writing poetry in a febrile Coleridge dream state. I lovingly immersed myself in it at every waking moment, for eight straight weeks in February and March of 2021; it’s one of the few poems that appears in both my collections.

I admit the section on Pasha is a curious interlude; the poem is made up of 74 couplets, and 68 of those couplets are about Evelyn McHale, a 23-year-old bookkeeper who committed suicide in spectacular fashion by jumping from the observation deck of the Empire State Building on May 1, 1947. Known in inimitable mid-20th century U.S.-tabloid-poetry as “the Beautiful Suicide,” McHale was the subject of a famous and arresting LIFE magazine photograph, lying in elegant repose in her pearls and white gloves; she’s seemingly asleep or unscathed from her dramatic leap (if it wasn’t for the demolished limousine serving as her funeral bier, and her shoeless feet.)

Originating as an ekphrasis of that photo, “Evelyn McHale Chooses the Tallest Building in the City” blossomed into an attempt at writing a Shirley Jackson short story along the lines of her 1957 story “The Missing Girl” or her 1951 novel Hangsaman, both prompted by Jackson’s obsession with the true story of Bennington college student Paula Jean Weldon, who mysteriously disappeared in 1946.

Hassan Pasha made it into my poem at the last minute. After weeks of researching McHale (tracking down family trees and contemporaneous records), writing her story in couplets (a speedy storytelling conceit I copied from poet Ross Gay’s flowing book-length poem about watching video of Dr. J Julius Erving’s famous NBA-finals-baseline-reverse layup), and then revising and revising, I decided it was time to cut off the obsession and finish the poem. My then-girlfriend, who I was quarantined with at the time, was tired of hearing about McHale; I was triangulating train timetables at 3 am, trying to track McHale’s exact movements on the day of her suicide. But I knew the poem wasn’t finished. Or more accurately, even though I decided I was done, I was still obsessing.

It was then that an easy research trope led me to Pasha.

One of the characters in my poem was the limousine driver who was fortuitously at a nearby drug store when McHale, like a Poseidon bolt, totaled his parked limo on W. 34th St. I had been captivated by the mention he got in the May 2 New York Times page 23 brief on McHale’s death, particularly liking the rhyme/slant rhyme rhythm of near-by/thereby/injury. “The driver was/ in a near-by drug store, thereby/ escaping death or serious injury,” which I turned into this couplet: “The chauffeur knew a drug store coffee counter/nearby, thereby he was free.” I figured he was probably reading a paper at that drug store counter, so, I looked up the May 1, 1947 New York Times to see if I could add some color to his cameo. Maybe some President Truman news would give the poem a dash of late 1940s verisimilitude.

Of course: What I found blaring at me from the PDF was a triple decker headline about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict: “Arabs Defeated, 8-1, In U.N./After Long Wrangle on Bid/For Independence Debate.” By of course, I mean God dammit. Obviously, my situation isn’t akin to being on the ground in Palestine or Israel, but as a progressive American Jew, this conflict has dogged me my whole life. P.s. High school history class and college campuses were unnerving for Jews back in the 1980s too, thanks to Israel.

God dammit because: Here I was experiencing my first euphoric, out-of-body, creative experience as a beginning poet, and once again, there’s no escaping Palestine for Josh. There was nothing to do but embrace it. And to be honest, it immediately felt right to do so. If I had to wrestle with this mindfuck tragedy my whole life, well then so did my epic poem. (I also took it as a good sign when it turned out the limo was a U.N. limo.)