An Electric Guitar Rendition

of my poem “I’m Delighted My Young Avant-Garde” by my old avant-garde friend.

My longtime YIMBY comrade Dan Bertolet has returned to his 1990s roots. Last week, he released a My-Bloody-Valentine-demos-style set of pop tunes prompted by teenage poet laureates such as W.B. Yeats, Sylvia Plath, Walt Whitman, e.e. cummings, and Robert Frost, along with a few other geniuses of verse: Louise Glück, Alice Oswald, and Wislawa Szymborska. He also sneaks in an Ocean Vuong poem! It’s an ambitious, shimmering 14-song set that Dan, going by Swirl & Ache (Frost), calls “Bonewebs, Hungry Seas, & Other Delights” (Oswald, I think).

Dan’s warm and plaintive vocals—featuring gracefully crafted recitative-like melodies—are word-for-word renditions of the poems. And the opening track is a rendition of one of my poems: “I’m Delighted My Young Avant-Garde Friend,” which was my attempt, back in 2019, to write a YIMBY villanelle.

Ultra teenage poet laureate Dylan Thomas wrote the famous villanelle “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” with the memorable repeated lines: “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night/Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” My pro-development version: “I’m delighted my young avant-garde friend/Let there be light, let there be infrastructure, amen,” which Dan leans into with a wicked overdrive guitar hook.

Here’s Dan’s explanation of his project:

“Hey there insta folks, I made some music and I guess it's good to share things that you make, so if you're game, copy/paste this bandcamp link:

https://swirlandache.bandcamp.com/album/bonewebs-hungry-seas-other-delights

”Over the past 16 months I got a bit obsessed with writing and recording little guitar pop ditties using other people's poems for lyrics. You all can blame @city_hex for getting me started.”

And here’s a recording of me reading the poem on the Cathexis Northwest web site back in 2021 (when it was first published.)

Poetry Journals are Published in the Spring

Secret discography.

I’ve been posting a new set of poems every quarter going back nearly six years. I don’t typically speak in terms of business calendars, but I started thinking in terms of quarters when my ex—a former Microsoft engineer and now do-gooder entrepreneur—asked me without any irony: “What quarter do poetry journals usually publish?” and I answered gleefully: “Poetry journals are not published in quarters? Poetry journals are published in the spring!”

You’re not supposed to post your poems publicly if you want them to appear in literary journals; I’ve been submitting my poems to journals regularly since March 2019, and I only posted my quarterly sets on a private blog. I’ve written 27 of these secret collections since starting with the 28-poem set Opposite Hex back in November 2017.

I just finished writing my Q1 2023 collection, This Sounds Perfect I Want to Find It. Again: I can’t share it here because I’ve submitted several of the poems to a bunch of literary journals.

As a way to catalog all these quarterly sets, though, I’m listing them below: The title of the collection (bolded and underlined), the date, and the titles of the individual poems; 289 poems to date.

A handful of these poems have since been published in the real world too, either in journals or in one of my two books. I’ve bolded those too and have noted where and when they appeared.

This Sounds Perfect I Want to Find It, January -March 2023

280. Weekend Crowds

281. Saturday, January 7

282. Parking Lot Orchestra

283. Vines

284. Metamorphoses

285. Tuesday, February 14

286. Hermes, I’m Only Dancing

287. The Turnstile Market RN

288. This Sounds Perfect I Want to Find It

289. Saturday, March 11

Let Your Side Hustle Shine, October – December, 2022

266. Biking and Woo-woo (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

267. Teenage Fragment

268. The Partridge Family Underworld Liberation Front (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

269. The Kindness of a Pharmacist

270. Vinyl, Mirror, Papyrus

271. Are They Friends of Your Daughter, Demeter? (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

272. By Possibility, I Mean

273. The Trip to My Parents’ House Used to be a Palindrome (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

274. Catasterism (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

275. I’m Not Telling Anyone I’m Here

276. Lust

277. Hermes, I’m Only Dancing

278. Thursday, December 22 (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

279. December 27th Thru January 1st

Isabel Eyeballs & Other Poems, July-September, 2022

248. The Woman in the Tide Pools Smiles (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

249. Mother of Demeter, Four Letters

250. Reaganism

251. Mistaken for Parks

252. Loops of leaves —Pentheus and Bacchus, Ovid’s Metamorphoses

253. The Scene of Scenes

254. Scene of Scenes

255. Last Night in Rockville, Pt. 1. Last Night in Rockville, Pt. 2

256. Testing for COVID at Midnight

257. When Poetry Arrives

258. Field of My Own

259. The Weight of Tram Wires in Lisbon

260. 14 Lines for Metropolitano de Lisboa

261. Isabel Eyeballs (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

262. Into the Parallel World

263. When Poetry Arrives

264. Uh oh. Someone Spilled Some Euros

265. Biking and Woo-woo (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

Only in Malady to Discover, April-June, 2022

240. To the 7-11

241. Saturday Night in the World

242. Only in Malady to Discover (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

243. Data Kid Dared Fate (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

244. Gifted

245. Five Best Falling Asleeps This Month

246. The Mystery of Mahmoud Hassan Pasha (revised)

247. The Woman in the Tidepools Smiles (publshed in my 2nd book, May 2023)

I’m Living My Best Sylvia Plath Life, January -March, 2022

230. Synesthesia Mistaken

231. A Tanka to Remember a Particular Friday Afternoon

232. The First View of the Earth from the Moon

233. Ancient City

234. A Tanka to Remember Our Ancient City (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in Novus Literary Arts Journal, May 2022)

235. Your Fine Beginnings

236. I'm Living My Best Sylvia Plath Life (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

237. The Spirit of the Food Truck

238. The Drum Machine at the Union

239. Aerodynamics

Lambent in the Hey Day of Different World, October – December, 2021

221. Coming Home Safe

222. What was Chuck Berry Thinking?

223. Vamp Philosophy

224. Instructions for Sabbath

225. Nervous System

226. The Night of Lady Day

227. Original DJs in Strife

228. U. District Station Tanka (published in my 1st book as “Infrastructure,” September, 2022 and published in Novus Literary Arts Review, May 2022)

229. It’s Projected to be the Biggest City in the World (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

The Night of Electric Bikes, July-September, 2021

213. Inevitably, Bildungsroman (published in my 1st book as “Athena Dethroned, September 2022 and published in my 2nd book as “Athena Dethroned,” May 2023)

214. These Flowers (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

215. Shadow Bus (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

216. Time at City Spectacles (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

217. Maybe Anemones

218. The Night of the Electric Bikes

219. City Exegesis (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in Novus Literary Arts Review, May 2022)

220. For New Year's Eve You Drew a Diagram (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

The Sidewalk is Parallel to the Sky & Other Poems, April -June, 2021

207. The Mystery of Mahmoud Hassan Pasha

208. The Sidewalk is Parallel to the Sky (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in High Shelf, April 2022)

209. Sonnet #5,659,674

210. A Different Kind of Light Left on, May Sarton (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

211. Having Just Been to the Graveyard Yourself

212. Obstacle Course (published in my 2nd book, May 2023 and published in Change Seven, October 2021)

I Swear They Were Here, January – March, 2021

200. Celebrant

201. Your Only Witness

202. Who’s Afraid of Susan Sontag?

203. New Year’s Resolution, January 2021

204. Urban Moon

205. Falsework (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

206. Evelyn McHale Chooses the Tallest Building in the City (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and in my 2nd book, May 2023)

Headstands with Nehru, October – December, 2020

189. In the Parking Garage Below, 16 Spots Open

190. Headstands with Nehru

191. Donald Trump Does Not Understand Elvis Presley

192. Seeking Narratives

193. The Young Pharmacists

194. Come In (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

195. L'histoire des émeutes

196. The Opposite of Fainting

197. Friday Per Se

198. Wayfinding (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

199. We are Now as Far Away

Essential Trips Only, July – September, 2020

177. An Epigraph Grows in Brooklyn

178. How to Change the Conversation

179. The Need for Renunciation (published in my 2nd book, May 2023 and published Vital Sparks, November 2021)

180. Adjusting Levels

181. An Appointment to Keep

182. Outer Space

183. Two City Perspectives (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

184. The Most Charming Time of Youth

185. Ode to My Teen Pottery Barn Faux-Fur Bean Bag Chair

186. Ms. DeMatteo's Art Class

187. There's No Longer an Excuse Not to Read the Autobiography of Malcolm X

188. Dave's Algorithm

Parks Without Fail, April – June, 2020

167. The Blooming Economy

168. Cities Not Gods

169. In the Course of Life’s Events (published in my 2nd book, May 2023 and published in Cathexis NW Press, December 2021)

170. In the Fields Upstairs

171. Arterial Turns

172. Leave This Meeting

173. Parks Without Fail

174. Electric Music for the Mind and Body

175. A Vegan’s Praise of Slaughter

176. The Defector

We Climb the Wild Hill Wary, January – March, 2020

157. Wayfinding on a Date with My Weird Girlfriend

158. The Airbnb of Innisfree (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

159. The Encyclopedia of Heresies (published in my 1st book, September 2022, published in my 2nd book, May 2023, and published in CircleShow, May 2020)

160. A Food Truck in the Old City (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

161. Bus Stop (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in Not a Press, October 2021)

162. Waveforms as They Are and as They Are Transformed

163. The Sound of the City

164. Sabbath Blesses Time Not Space

165. We Climb the Wild Hill Wary

166. Linc Wheeler Parking Lot

164. The Pizza Principle

165. Guest House

166. The Innisfree Light Rail Extension (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

I Decided to Take the Day Off Work, October-December, 2019

150. A Question of Their Own

151. Teen Titans

152. Afternoon at Rest

153. Upside Down Cross of Gold Speech

154. "What are the Words to White Man?" (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in the Halcyone Literary Review, June 2020)

155. Reliquary

156. Ric Ocasek Dream

Enchiladas are Served, August-October, 2019

144. The Transcontinental Railroad

145. Such a Great Ass Saturday

146. The Coronation of Summer (published in my 2nd book, May 2023, and published in the Lily Poetry Review, February 2020)

147. Linger Factor (published in my 1st book, September 2022, published in my 2nd book, May 2023, and published in Vallum, April 2021)

148. Sidewalk Plaque (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

149. Orange Julius

Shops Close Too Early, June & July, 2019

134. Home Remedy

135. Doldrums

136. Leave of Absence

137. From the Airport

138. If I Were Rich, I Would Commission Artists to Save the Cities (published in my 1st book as “Patron of Geography,” September 2022)

139. Word on the Street

140. Bunna Café

141. TBONTB (To Be or Not to Be) 1983

142. Dreaming After Reading Louise Glück

143. Dreaming after Reading Sylvia Plath

The Light Rail Blues & Other Planning Poems, Spring 2019

124. Teen Vogue Published My Villanelle

125. Station Access Planning (published in my 1st book as “Blue Balcony,” September 2022 and published in Bee House as “Blue Balcony” in August 2020)

126. Five Years

127. 1981

128. Not Even the Bernie Sanders/Hillary Clinton Debate Can Ruin This Perfect Day

129. 300 Riverside Drive

130. The Pedestrian Blues

131. Concerning Human Remains

132. The William Carlos Album Blues

133. The Green Piano

Outside, They’re Making All the Stops, February, March, April, 2019

116. I'm Delighted, My Young Avant-Garde Friend (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in Cathexis Northwest Press, December 2021)

117. Tehran Mary

118. Threepenny Policy Paper

119. Revelation to Genesis (published in Cathexis Northwest Press, October 2019)

120. On & Off

121. Lapsed Vegetarians

122. Lunch w Your Ex

123. City Planning Pantoum (published in my 1st book, September 2022, published in my second book, May 2023, and published in High Shelf, July 2019. This was the first poem I got published.)

Seven Modes of Thanksgiving, b/w Listen Closely Robot, November-December 2018

Seven Modes of Thanksgiving

97. Seven Modes of Thanksgiving

98. Tuesday

99. Wednesday

100. Thursday

101. Friday

102. Saturday

103. Sunday

104. Monday

Listen Closely, Robot

105. West Side Side Story

106. Feminism

107. The History of Fare Enforcement

108. Elf Power (published in my 1st book, September 2022, published in my 2nd book, May 2023, and published in Spillway, September 2019. This is the first poem I got accepted. It was accepted in April 2019.)

109. Marxist Decision

110. I’m Trained to See These Things

111. Sunday Night in a Blue City

112. Hafiz is the Guest of Honor at Hanukkah Dinner

113. Dinner (published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

114. Friday Night Orchestra

115. Safe House (January, 2019)

Center Platform, October-December, 2018

90. A Poem for My Daughter

91. Phenomenon

92. Whoever is Running Sound for this Dream

93. Center Platform

94. Pay Attention

95. Johnny Forget Keeps Track

96. Amy, Sad, Ranjit, Alyssa, Ann, & Paul

Flip the 26th, September-October 2018

80. Design Build

81. Jerry Garcia, You’re Tagged in this Tweet

82. A Science Fiction Novel I Will Write

83. Amplitude in the Micro Apartment

84. After the Dynasty

85. A Side of Black Beans Saves the Universe

86. On a Device Similar to a Ouija Board

87. Dead Sea Sonnet

88. Lax as AF

89. Bonus Single: 13 Ways of Seattle (Dub Version Remix)

The Subway Arts Movement, July -September, 2018

65. The Subway Arts Movement (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

66. Mode Fetishist

67. Fainting Spells

68. Art Transit

69. Down in the Tube Station at Midnight, East Coast Time

70. Families in Motion

71. City Arts Movement

72. Split Level

73. Stealth 4-Plex

74. Witchcraft Oriented Development

75. Peace in the Middle East or at the Columbia City Farmers Market, at Least

76. The City, Pro Se

77. A Good Ass Saturday

78. Welcome to the Night Market

79. Playing Hooky

When Headways are No Longer Measured in Buses, April-July, 2018

49. When Headways are No Longer Measured in Buses

50. You Had Me at Transport, Emily Dickinson (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in An Evening with Emily Dickinson/Wingless Dreamer, June 2021)

51. Crush Load (published in my 1st book, September 2022)

52. Last Night, the Mentalist

53. You May Also Like, 2018

54. Thirteen Ways of Seattle

55. Jewish Book Store, 11250 Georgia Ave. Wheaton, MD., 1971

56. Governance

57. Dance of the Seven Veils

58. Jews Will Not Replace Us

59. This Ain't No Disco

60. The Piano Teacher Said

61. Wrap My Arms Around the Parking Lot

62. A Tale of 2 Picnics & 1 Day-Glo Satanist

63. Heading Out the Door

64. Pedestrian Contradiction

Fear of Memphis, January –April, 2018

39. Dwell Time (published in my 1st book, September 2022, published in my 2nd book, May 2023)

40. Fear of Memphis

41. Ons & Offs

42. Advice to Robert Mueller (April, 2018)

43. I Can Never Quite Explain Why

44. Dub Shabbat

45. Chet Baker Version

46. The Official Remix

47. Nostalgia

48. Jenny Says to Revelate

Five More Poems, December, 2017

34. 1356 flat7 653

35. A History of Smart Girls

36. Dear, Bar Stool Historians

37. After Extensive Research

38. A History of the City

The Neighborhood Planning EP, December 2017

29. I Didn’t Predict Any of This (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in The Halycone Literary Review, June 2020)

30. Downtown is an Offset

31. How is This Year Going to End?

32. Neighborhood Planning

33. I Don’t Miss Journalism

Opposite Hex, August -November 2017

1. The Suburbs

2. Down with it, Innocence

3. Absolute Flâneurs

4. Piano Teachers Row

5. Checklist for Her Setlist

6. Opposite Hex

7. Water the Plants

8. Teenage Time Machine

9. Five Examples of Urban Alchemy

10. 22nd Avenue Greenway

11. Cosmic Lee & Me Still Hate Reagan

12. Seamless Summer

13. Annual Report

14. Desire Bench (published in my 1st book, September 2022 and published in Not a Press, October 2021)

15. Three Penny Theory

16. Purge City

17. The Case for Making Drivers Pay to Enter Downtown

18. I’m Looking Forward to What You Do

19. Environmental Benefits Statement

20. When You’re Sad on Sunday Night

21. Rebellions Embedded in Infrastructure

22. When the Cement Falls Off My Face

23. For the Worse?

24. Parking Dharma

25. Incidental Use

26. The City Canon

27. I Want to be Close

28. City Council Endorsement

Other Seismic Moves Include…

No address there and bare,

but where once Love,

Sloths,

Seeds

played a place called Pandora’s Box.

NYT opinion writer and Columbia University professor James McWhorter has a piece in today’s NYT citing 1966 as the year woke politics emerged.

Agreed. I’ve always believed that my birth year, 1966—the year the Black Panther Party was founded, the year the National Organization for Women (NOW) was founded, the year the Velvet Underground was in the studio recording their first LP— was a Before-and-After year.

In fact, I have a poem about one of the many explosive events that took place in ‘66: The Sunset Strip Curfew Riots, which I believe were a herald and catalyst for merging two ascendant 1960s phenomenon—rock music culture and youth politics—into a more defined counterculture. Side note: The riots—which grew out of an L.A. rock radio station’s call to protest City Hall’s curfew crackdown on Sunset Strip’s teen music scene—also inspired the famous ‘60s tune: “Stop, children, what’s that sound, everybody look what’s going down…” (It’s a tune the aforementioned Velvet Underground probably scoffed at, but for what it’s worth, it becomes clearer and clearer as the decades go by that the seemingly disparate cultural factions of that time were part of the same change-agent movement.)

McWhorter’s essay is specifically about the shift in tone the Civil Rights movement took on that fateful year.

He begins:

The difference between Black America in 1960 and in 1970 appears vaster to me than it was between the start and end of any other decade since the 1860s, after Emancipation. And in 1966 specifically, Stokely Carmichael made his iconic speech about a separatist Black Power, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee he led expelled its white members (though Carmichael himself did not advocate this), the Black Panther Party was born, “Black” replaced “Negro” as the preferred term, the Afro went mainstream, and Malcolm X’s “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” (written with Alex Haley) became a standard text for Black readers.

Happy that a New York Times column was giving my pet theory about 1966 some play, I emailed McWhorter.

Josh Feit <jfeitinwords@gmail.com>

5:47 AM

to jm3156

Mr. McWhorter,

As a partisan '66er (I was born in 1966), I've long believed it was a

jump cut year in cultural history, and my bar stool theory always

cited Stokely Carmicheal's historic June '66 "Black Power" exhortation

in Greenwood, MS as the main example.

So, thank you for your piece.

As you are likely well aware, other seismic '66 moves include: Betty

Friedan and (Civil Rights leader) Pauli Murray founding NOW; white pop

music flirting with the avant-garde as it shifted from bubble gum to

psychedelia (Beatles' Revolver, Byrds' 5D, Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, and

the Velvet Underground record their historic debut, for example);

Ralph Nader (and the corporate accountability movement) emerged with

Unsafe at Any Speed (December, 1965, but his famous congressional

testimony based on the book comes in '66); and the first LGBTQ riot (3

years before Stonewall) at San Francisco's Compton's Cafeteria, among

many other breakthroughs and mood shifts.

I recently published a book of poems (about transit, city planning,

and YIMBY politics, actually), but one poem in the collection,

"Sidewalk Plaque"—about the "Curfew Riots" on the Sunset Strip in

November, 1966—attempted to place that moment in context of the

zeitgeist. It definitely includes a line about Carmichael.

I've attached the poem. I hope you enjoy it.

Sincerely,

Josh Feit

Sidewalk Plaque

The #2 bus pulled up to Sunset & Crescent Heights. Google Maps said I’d arrived. The destination is on your right.

Sightseeing in L.A. I’d arrived at a Chase Bank, a drive-through branch, fronting a strip mall parking lot. But the afternoon’s real destination was the adjacent traffic island.

No address there and bare, but where once Love, Sloths, Seeds played a place called Pandora’s Box. (City Hall had worried Pandora’s myth was coming true on Sunset Strip. The kids were hopeful about this too.)

Their curfew riot was one of many Constitutional amendments that year. Pauli & Betty starting NOW. Stokely saying “Power.” The riot at Compton’s Cafeteria.

Compton’s Cafeteria no longer exists, but at least there’s a plaque on the sidewalk.

Compton’s

Cafeteria Riot 1966

Here marks the site of

Compton’s Cafeteria where a riot

took place one August night when

transgender women and gay men

stood up for their rights and fought

against police brutality, poverty,

oppression and discrimination

in the Tenderloin

There’s no plaque at the barren traffic island on Sunset Strip.

Allow me:

Pandora’s Box

Curfew Riot 1966

Here marks the site

where

night

stood up.

You have arrived. Your destination is found in others.

Get on the Syllabus: What I’m reading and where it takes me.

What I’m reading and where it takes me.

2024 —

Ursula Parrott, Ex-Wife , ©2019

Chris Stein, Under a Rock , ©2024

With his glitter makeup and long hair tales of living off welfare in abandoned lofts, playing bit parts in art film flops, and doing drugs with his band scene pal, precursor punk faerie rocker Eric Emerson, Chris Stein’s stories from early 1970s Lower East Side Manhattan overlap with Murger’s 1840s fables from the Left Bank.

With his first person account of the endlessly fascinating era when hippies were transforming into punks in NYC’s downtown art scene, Stein, who has a charming, humble and earnest online presence today, by the way, is working with rich source material (like the day in 1973 when his girlfriend Debbie Harry comes back to her Little Italy apartment from her job at a New Jersey salon with her hair dyed blond.)

Unfortunately, despite the perfect bohemian trappings, Stein writes with zero craft or reflection and the book reads as if he simply hit record and proceeded to reminisce without purpose. I have no idea, for example, why Stein loves, or even plays music in the first place. Or, for that matter, how his high school band ended up opening for the Velvet Underground.

Alas, I’m reading every word.

From 1975: “We went to some guy’s basement recording studio in Queens. Nobody had a clue where we were… It was miserably hot in the basement but we managed to get five tracks done, including a version of what would later evolve into ‘Heart of Glass.’”

Henri Murger, Scenes of Bohemian Life , ©1851

This is a hilarious precursor to all the (more serious) urchin chic fiction I love. I’m not sure why it took me so long to finish reading it.

Here’s what I wrote about it when I first started it in June, month ago. And with exception of wanting cite more of the constant side-splitting one-liners (which constitute every three lines of every story) and noting that it does offer a more serious side towards the end with Mimi’s death (and the great one-off short story about Francine’s death), my original account is captures it:

My own private city studies seminar (which last year, focused on mid-19th Century Industrial Revolution Manchester novels such as Elizbeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton and Charles Dickens’ Hard Times, and this year, seems to be focusing on 21st Century Lagos novels such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah and Damilare Kuku’s Nearly All the Men in Lagos are Mad), has suddenly returned to the 1850s, though not to Manchester.

It’s Paris this time.

I’m reading Henri Murger’s 1851 Scenes of Bohemian Life. Murger’s novel (more a collection of short stories starring a recurring crew of Latin Quarter young souls in their charming, starving-artist garrets) was the source material for Puccini’s famous 1896 opera La bohème.

I’m only 10 stories in, there are 23 in the collection, and to my surprise, as opposed to more bittersweet urchin chic literature like Bertol Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, or my favorite urbanist novel, Colin MacInnes’ Absolute Beginners, this seems to be an all-out madcap comedy.

It’s as if the Marx Brothers were the main characters in 1001 Arabian Nights. The Marx Brothers in this instance being Rodolphe the poet, Marcel the painter, Schaunard the musician, and Colline the philosopher, gallivanting and stumbling their way through offhanded urban parables, constantly in need of rent (or date) money while pursuing their Quixotic masterworks, such as Marcel’s grand painting “The Passage of the Red Sea.”

A perfect example of Murger’s sit-com chaos plays out in the story “The Billows of Pactolus.” In this installment of Rodolphe, Marcel, Schaunard, and Colline’s merry poverty, named after a river from Greek mythology laced with gold ore sediment (presumably making its riches hard to grasp), Rodolphe suddenly comes into some money (500 francs!) and sets out to “practice economy” with the convoluted logic of a dreamer: the first thing he buys with his windfall is “a Turkish pipe which he had long coveted.”

""This is my design. No longer embarrassed about the material wants of life, I am going seriously to work. First of all, I renounce my vagabond existence: I shall dress like other people, set up a black coat, and go to evening parties. If you are willing to follow in my footsteps, we will continue to live together but you must adopt my program. The strictest economy will preside over our life. By proper management we have before us three months' work without any preoccupation. But we must be economical."

"My dear fellow," said Marcel, "economy is a science only practicable for rich people. You and I, therefore, are ignorant of its first elements. However, by making an outlay of six francs we can have the works of Monsieur Jean-Baptiste Say, a very distinguished economist, who will perhaps teach us how to practice the art. Hallo! You have a Turkish pipe there!"

"Yes, I bought it for twenty-five francs."

"How is that! You talk of economy, and give twenty-five francs for a pipe!"

"And this is an economy. I used to break a two-sous pipe every day, and at the end of the year that came to a great deal more."

"True, I should never have thought of that."

They heard a neighboring clock strike six.

"Let us have dinner at once," said Rodolphe. "I mean to begin from tonight. Talking of dinner, it occurs to me that we lose much valuable time every day in cooking ours; now time is money, so we must economize it. From this day we will dine out."

"Yes," said Marcel, "there is a capital restaurant twenty steps off. It's rather dear, but not far to go, so we shall gain in time what we lose in money."

"We will go there today," said Rodolphe, "but tomorrow or next day we will adopt a still more economical plan. Instead of going to the restaurant, we will hire a cook."

"No, no," put in Marcel, "we will hire a servant to be cook and everything. Just see the immense advantages which will result from it. First of all, our rooms will be always in order; he will clean our boots, go on errands, wash my brushes; I will even try and give him a taste of the fine arts, and make him grind colors. In this way, we shall save at least six hours a day."

Five minutes after, the two friends were installed in one of the little rooms of the restaurant, and continuing their schemes of economy.

"We must get an intelligent lad," said Rodolphe, "if he has a sprinkling of spelling, I will teach him to write articles, and make an editor of him."

"That will be his resource for his old age," said Marcel, adding up the bill. "Well, this is dear, rather! Fifteen francs! We used both to dine for a franc and a half."

"Yes," replied Rodolphe, "but then we dined so badly that we were obliged to sup at night. So, on the whole, it is an economy."

Needless to say, abiding by their delusional budgeting scheme, they promptly go broke. As the story concludes (and after firing their costly servant), Rodolphe muses: “Where shall we dine today?'“ and Marcel replies, “We shall know tomorrow.”

Emma Cline, Daddy , ©2020

I turned to one of my favorite contemporary novelists, Emma Cline—The Girls (2016), The Guest (2023)—to jar me out of my recent reading slump. And it worked. In this instance it was short stories, her riveting 2020 collection, Daddy.

Given that most of the 10 dark stories here play out in proximity to male violence—or the ubiquitous possibility of male violence—the title, as my book store bestie Valium Tom suggested, seems to be a Sylvia Plath reference. Otherwise, the only explicit reference to “Daddy” here comes in the final story “A/S/L” (sex hookup slang for “Age, Sex, Location”) as the online handle—”DaddyXO”— of Thora, a woman who spends all her time catfishing oafish men. The listless wife of a non-descript, “not a bad person”-husband named James, Thora lies awake texting “furtively on her phone…while James slept, his back turned to her” posing as an 18-year-old high school cheerleader. The story is set, presumably after Thora crashes and burns from her phone sex addiction, in a high-end rehab facility where she then contemplates seducing a famous Me-Too’d TV chef, “G”—who has landed at the facility as well. Thora is exactly the kind of damaged soul who inhabits Cline’s fiction.

However, the majority of the stories, the best of them set in Cline’s flawless simulacrums of ennui-laden, Slouching Toward Bethlehem Southern California, feature men as the despondent central characters: a diminished abusive 60-something father who is bemused by his distant and aimless adult children during their annual holiday season visit home; a Me-Too-disgraced magazine editor now groping through a pity assignment working on a book by a wealthy tech/lifestyle guru, and then botching the rare career opportunity by aimlessly hitting on the guru’s assistant; a divorced, fading movie producer suffering through his surfer-bro son’s banal directorial debut during a tacky theater rental screening; a simmering and distant father (with an alcohol and opioid addiction) called in to rescue his troubled, violent son after the boy gets expelled from an elite private school.

And, in the collection’s showstopping story, “Arcadia” (originally published in Granta and which I actually first read in The Best American Short Stories 2017), one of the few characters here who appears to have a moral center: an earnest boyfriend/live-in farmhand navigating the fraught household of his pregnant girlfriend and her erratic and frightening older brother, who owns and runs the farm.

Like much of today’s short fiction, Cline’s stories remain mum on specifics, only hinting at the crux of the conflict at hand while preferring to linger in deceptively casual dialogue, quietly startling observations, and the minimalist realism of daily lives. The understated stories usually include a dramatic scene too, well-placed land mines that offer some sort of allegory when their explosive glare sheds light on the otherwise repressed narratives.

Cline is a master of this form, particularly pivoting to violent scenes—the impromptu dentistry in “Marion” (which struck me as an early draft of Cline’s Manson Family novel The Girls), or most notably, a terrifying porn-inspired night, drunkenly orchestrated by the dangerous aforementioned older brother in “Arcadia.”

It’s the quality of Cline’s keen observations, with their crisp verisimilitude, that make her stand out from the pack of writers working in this style of enigmatic storytelling. Whereas most writers—I’m thinking of Sally Rooney—tend to tack on observations that fall outside of the scene (I jest, but something akin to, “a crash of thunder sounded in the distance…”), Cline’s breadcrumb asides—"We sat in the back of Bobby’s pickup as he drove the gridded vineyards and released wrappers from our clenched fists like birds” … “‘Home around five,’ she said… [loosening] her hood, pulling it back to expose her hair, the tracks from her comb still visible….”—feel intrinsic to the action at hand while simultaneously commenting on it.

What also makes Cline stand out from the pack, is this: While feminist at their core, her stories are deeply sympathetic to both women and men (who she seems to have a surprisingly uncanny inside track on) as she portrays both genders as trapped in the manufactured doubts scripted by societal roles, but also born of the stultifying human condition.

(I wrote a review of Cline’s second novel, The Guest, last year, which also includes a lot of thoughts about her first book The Girls. Scroll down down down to find that review.)

Jos Charles, a Year & other poems, ©2022

These poems are songs; rhythms punctuated by gorgeous phrases that have an effortless way of finding the contradictions afloat in the subconscious: ”between the hole of/a stone & dove within it;” “Let us hold a coconut It is dusk;” “canopies of collapsing light;” “I put you into a poem/you climbed the giantest tree/I put a dozen grapefruit into a tree/You ate every one.”

It reminded me of the obscure imagery and shrouded narratives you find in cryptic John Ashbery poems. It’s all a bit bewildering.

I read Charles’ (Pulitzer nominated) 2018 book of poems Feeld back in 2020 and remember feeling the same way; though in Feeld, she embraced the rhythmic trance and cryptic meanings to the point of creating a brand new language. A gorgeous feat. Unfortunately, I didn’t find nearly as much of that here.

Erin Williams, Commute, ©2019

Incredibly brave and startlingly vulnerable. But she doesn’t translate this diary into a new or larger narrative.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Americanah, ©2013

So much hype and this was disappointing. There was too much telling and not enough storytelling.

And most of the telling, while undeniably true and important, was well-tread talking points about the tangible, systemic walls and everyday slights that make life for Black people in America a barbed wire fence of challenges. Again. Undeniable analysis. But not new nor shown here.

Damilare Kuku, Nearly All the Men in Lagos are Mad, ©2021

I have been searching for the great Lagos novel;Teju Cole’s thoughtful Every Day is for Thief (scroll down for my review) wasn’t grand enough to fit the bill.

I’d hoped Nigerian Nollywood movie maker, actress (that’s how she describes herself) and creative artist, Damilare Kuku was en route to pulling it off with her 2021 short story collection, Nearly All the Men in Lagos are Mad, which is just now being published in the U.S.

And while it is an addicting collection of reverse-rom-com tales (the affairs do not work out here), the stories felt more like binge-era-TV pilot episodes than literature.

This might not be the classic I’m looking for, but indeed, I did binge. This is a flippant, fast-paced book; I read all 12, neatly crafted, 20-page stories (which often experiment with narrative POV, including rotating narrators and even some Bright Lights, Big City second person) in a few delightful sittings this week.

Certainly, Kuku’s candid, mostly female narrators—no-nonsense entrepreneurial strivers who fall for good looking lover boys with rizz and fatal flaws—convey the tragicomic condition of life in Lagos for women caught up (along with their guardian angel, best girlfriends) in the go-go capitalist patriarchy that fetishizes them as both subservient wives and party girls.

Set against Lagos’ backdrop of lush compounds and first-time apartments, clubs, scandalous texts, social media melodrama, ubers and public transit, nepotism, hustles, corruption, starter jobs and start ups, Kuku’s city stories focus on wary characters whose inner monologues ruminate on class, raunchy sex, tragic pasts, toxic family dynamics, love, and lousy men (even the sensitive guys.)

The breezy, pop culture tone and rushed, tidy finales interrupt Kuku’s frequent literary and philosophical turns, so I’m hesitant to recommend it. But, admittedly, I’m recommending it.

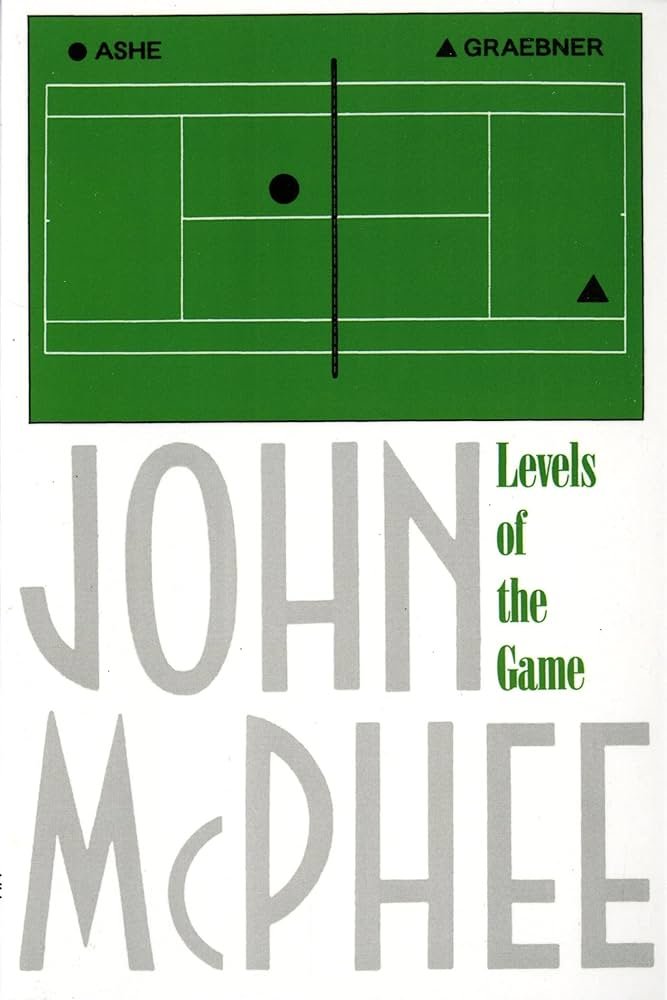

John McPhee, Levels of the Game, ©1969

I wrote about this book on my I’m All Lost In post for the week of 3/1/24-2/8/24:

I devoured 70 pages of Levels of the Game, John McPhee’s literary dispatch from the 1968 U.S. Open, in one sitting on Monday night.

Originally published serially in the New Yorker in 1969, Levels of the Game is a minutely and lovingly detailed account of the semifinal match between tennis legend Arthur Ashe, (“his body tilts forward far beyond the point of balance”) versus Clark Graebner, Ashe’s bruising, top-ranked, opponent. Ashe wins and goes on to become the first African American to win the Men’s U.S. Open.

McPhee approaches sports writing as if he’s Sherlock Holmes, seamlessly combining a meticulous tennis-match details—”He takes his usual position, about a foot behind the baseline, until Graebner lifts the ball. Then he moves quickly about a yard forward and stops, motionless, as if he were participating in a game of kick-the-can and Graebner were It…”—with the slow motion backstories that inform each volley: “‘It’s very tough to tell a young black kid that the Christian religion is for him,’ he says. ‘He just doesn’t believe it. When you start going to church and you look up at this picture of Christ with blond hair and blue eyes, you wonder if he’s on your side.’”

For me, McPhee’s crack reporting skills—he knows exactly how Graebner places his feet when he brushes his teeth in the morning—confirmed McPhee’s revered status as a progenitor of creative non-fiction.

Those reporter’s chops are certainly on display as McPhee conjures Ashe’s childhood with evocative quotes from Ashe (“The pool was so full of kids in the summer you couldn’t see the water”), to his research into Ashe’s junior games (“he read books beside the tennis courts when he wasn’t playing,”) plus a wonderful anecdote from a high school date about Ashe’s “antique father.” He does all this right alongside the immediate tennis play-by-play (“a difficult, brilliant stroke, and Ashe hit it with such nonchalance that he appeared to be thinking of something else”), while adding his transcripts of the rivals’ internal monologues: ”Graebner dives for it, catches it with a volley, then springs up, ready, at the net. Ashe lobs into the sun, thinking, ‘That was a good get on that volley. I didn’t think he’d get that.’”

And he serves quiet axioms along the way: “Confidence goes back and forth across a tennis net like the ball itself, and only somewhat less frequently.”

One disappointing oddity: For a book about such a turbulent era, McPhee writes with a square, AM radio voice; as a result, a time that is decidedly connected to our own is rendered strangely remote here.

That said, it’s a pleasure to disappear into a lost world drawn so vividly.

———

I’d add that the in the final 30 pages or so, McPhee directly addresses the “Black Militant” politics of the time—or quotes moderate Ashe on the subject; keeps rolling with the internal monologues; and has a lovely locker room scene before the final set when the Davis Cup coach (Ashe and Graebner are both on the U.S. team) visits each player separately to give them last-minute advice.

Sheila Heti, Alphabetical Diaries, ©2024

I wrote about this exciting book in my weekly obsessions post, I’m All Lost In :

I still remember reading an excerpt from Alphabetical Diaries, Sheila Heti’s innovative memoir two years ago when the NYT ran a preview — and how it struck me that her writing should be filed under poetry rather than memoir.

When I saw that the book finally came out this month, I had to buy a copy.

Innovative how? Heti downloaded a decade-worth of journal entries into an Excel spreadsheet and re-sorted it alphabetically by the first letter of each sentence.

From Chapter 9, for example:

I have never been so screwed for money, and I am angry at Lemons for not returning my emails. I have never known what a relationship is for. I have never worn such dark lipstick before. I have no money. I have no one. I have spent the whole night in my hotel room, eating chocolate cereal. I have started playing Tetris, which feels halfway between writing and drinking.

While the effect can be a bit like refrigerator magnet poetry—with entire sentences instead of single words—Heti’s idea that “untethering” her lines from their original chronological narrative “would help me identify patterns and repetitions…How many times had I written, ‘I hate him,’ for example?” works as exegesis for the reader as well. By scrambling the traditional notion of a diary, often comically so, Heti’s non-stop and remarkable juxtapositions reveal how life’s epic and mundane moments intertwine—indistinguishably at times—to create a super-narrative distinct from specific plot twists.

It’s a useful, and ironic directive (from a diary!), to get out of one’s own head and notice the larger stories that define us.

I’m only on Chapter 14, N, which begins, “Neglect my friends and family. Never having felt so sad. New sheets for the bed. New York, I think, made me depressed…” but I will have surely finished the whole book by the time you read this. I’m addicted to the clipped rhythm that’s transforming Heti’s non-sequitur flow into a logical story. It’s as if each sentence is commenting on the preceding one. Glued to her “untethered” account, I’m dying to see what happens next.

Heads up—not that this going to ward anyone off—these diaries are salacious.

————

And having finished it now, here’s what I’d add:

Late in the book, in the W chapter, Heti breaks from her steady, minimalist cadence and rolls out a run-on sentence (a fantastically specific description of a woman on a 13-hour train ride, the person Heti wants to write a novel for) that’s simultaneously anxious and calm—the sentence, not the woman—which, with its meta overtones, is, as much as possible, a summary of the character we’ve come to know after immersing ourselves in her musique concrète diary revision.

Also: Affirming that this instructive lesson about the human condition is inseparable from a personal, intimate, and vulnerable autobiography, late in the T chapter, Heti outdoes the salacious standard she’d already set with a super risqué account: “This was the weekend that Vish hog-tied me, fucked me up the ass for the first time, …”

She closes the book with a playful sentence about Zadie Smith’s husband, the lone sentence in chapter Z.

Jane Wong, How To Not Be Afraid of Everything, ©2021

This book of excellent poems topped this week’s (2/16-2/23) I’m All Lost In post, my regular roundup of current obsessions. Here’s what I wrote about it:

Wong’s poetry splices her outcast biography—mostly her formative experience in white America/”the Frontier” (growing up poor with a Chinese immigrant mom and derelict, alcoholic father)—into the harrowing history of her grandparents’ crushed lives under Mao.

She still speaks to them: “Was I a pigeon in this city in your dream? Were you/ hungry when dreaming?” And they still speak to her: “…I can only hear the vowels of your questions,/your fists curling and uncurling in sleep, the low rush of wind along ferns so tall—they must be pulled up by the sky.”

Wong is a master of the fine detail (”a butterfly crawls into a chip bag;” “fruit flies fluttering about like snow;” “my father’s ruined jaw/misshapen like a novice ceramist’s bowl”); the liberating revelation (”let all your hexes seep into your pores;” “beware of light you cannot see;” “leave any country that has a name”); and sumptuous mic drops (“Serenade a snake and slither its tongue/into yours and bite. Love! What is love/ if not knotted garlic”).

Her evident talent effortlessly lifts her verse beyond politics into poetry. An uncommon skill!

Marking my favorite poems in this collection with stars became redundant, but there’s definitely this one:

I Put on My Fur Coat

And leave a bit of ankle to show.

I take off my shoes and make myself

comfortable. I defrost a chicken

and chew on the bone. In public,

I smile as wide as I can and everyone

shields their eyes from my light.

At night, I knock down nests off

telephone poles and feel no regret.

I greet spiders rising from underneath

the floorboards, one by one. Hello,

hello. Outside, the garden roars

with ice. I want to shine as bright

as a miner's cap in the dirt dark,

to glimmer as if washed in fish scales.

Instead, I become a balm and salve

my daughter, my son, the cold mice

in the garage. Instead, I take the garbage

out at midnight. I move furniture away

from the wall to find what we hide.

I stand in the center of every room

and ask: am I the only animal here?

William Wordsworth, Selected Poems 1793-1850, ©2004

My recent foray into 19th century literature—Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton, Charles Dickens’ Hard Times, Friedrich Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England, and Thomas DeQuincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater—all from a subset of my self-induced City Studies Seminar— has led me down another autodidact path: 19th century poetry.

(Just like the city syllabus, my 19th century poetry reading list is research for my all-consuming poetry practice.)

I led off this 1800s poetry inquiry with William Wordsworth.

His idyllic and philosophical nature poetry, which, channeling the age-old and persistent Babylon trope, casts cities as havens of corruption and inauthenticity—”Love cannot be; nor does it easily thrive/In cities, where the human heart is sick/” (The Prelude, Book 12, Same Subject)—certainly seems at odds with my own pro-city, city-planning poetry; and, by the way, his religious reverence of nature comes with the trite and adjacent narrative that fetishizes childhood .

But Wordsworth’s 100% gorgeous writing (“the stars have tasks”; Gipsies); his calm strong suit, writing verse as short stories —The Ruined Cottage, The Brothers, The Thorn, Michael, Idiot Boy); and the larger space-time continuum philosophy that governs his scenic Romanticism, all render my political disagreements with his pastoral odes irrelevant.

In fact, I found Wordworth’s nature walks—”I love a public road…like a guide into eternity…” (The Prelude, Book 12, Same Subject)—simpatico with my own city strolls. Wordsworth is a great flaneur.

All his vales and crags and nooks and “foxglove bells” (Nuns Fret Not at Their Convent’s Narrow Room) aside, what always seems to be at the heart of his sylvan perambulations are the characters, the freaks (!) he invariably meets along the way: noble beggars, ghosts, orphans, leech collectors, spooky kids, gipsies, sailors, ancient men; and mysterious women with “a tall Man’s height, or more….” in “ a long drab-colored cloak” (Beggars).

Coincidentally, Wordsworth is also drawn to the the exciting characters of the city; in fact, in the finale of The Prelude, Book 7, Residence in London, he exalts the street entertainers that define his crowning metaphor of the city’s “press of self-destroying, transitory things.”

His “Parliament of Monsters” is pure urban exhilaration:

The hurdy-gurdy, at the fiddle weaves,/

Rattles the salt-box, thumps the kettle-drum,/

And him who at the trumpet puffs his cheeks,/

The silver-collared Negro with his timbrel,/

Equestrians, tumblers, women, girls, and boys,/

Blue-breeched, pink-vested, and with towering plumes./ — All moveables of wonder, from all parts,/

Are here — Albinos, painted Indians, Dwarfs,/

The Horse of knowledge, and the learned Pig,/

The Stone-eater, the man that swallows fire,/

Giants, Ventriloquists, the Invisible Girl,/

The Bust that speaks and moves its goggling eyes,/

The Wax-work, Clock-work, all the marvellous craft/

Of modern Merlins, Wild Beasts, Puppet-shows,/

All out-o'-the-way, far-fetched, perverted things,/

All freaks of nature, all Promethean thoughts/

Of man, his dulness, madness, and their feats/

All jumbled up together to make up/

This Parliament of Monsters. /

No wonder in the next chapter of The Prelude, Book Eight, Retrospect. — Love of Nature Leading to Love of Mankind, Wordsworth sounds like city zealot, poet Frank O’Hara:

“London!”—O’Hara would say Manhattan— “to thee I willingly return./Erewhile my Verse played only with flowers.”

Yes, I’m cherry picking lines. Wordsworth exclusively reveres the “internal feelings” of dandelions, the “gentle agency of natural objects,” (Michael) his “darling Vale!” and the “active universe” (The Prelude, Book Two), and regularly returns to his overarching idea that glimpses of the glorious natural world and its “gem-like hues!” (Ode Composed upon and Evening of Extraordinary Splendor and Beauty) sustain us during the otherwise downcast prison of the daily world.

Wordsworth’s topic isn’t my thing, but his subject is.

In Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth channels his “wild green landscape” to cast light on the “unintelligible world”:

Almost suspended, we are laid to sleep/In body, and become a living soul/…We see into the life of things.

I have been enamored with this collection—and its non-stop reservoir of possible epigraphs—all January and February, writing about it along the way here, here, here, and here.

2023—

Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Barton, ©1848

Fans of Manchester novels, a sub-genre of Victorian fiction that explicitly deals with owner-worker conflict during the Industrial Revolution, undoubtedly put Charles Dickens’ novel Hard Times and Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel Mary Barton on their lists of classics.

Of all the similarities between these two Communist Manifesto-era standard-bearers—the beshitten backstreets, the righteous working class heroes, the saintly women, the pompous, oblivious privilege of the master class—one curious plot device quietly figures in both novels: the good guys’ unquestioned decisions to shield a family member from the law. In Hard Times, the nearly spectral protagonist Loo Gradgrind helps her remorseless, selfish brother, Tom Jr. elude the police after he embezzles money from his fancy bank job. And in Mary Barton, hero Mary conceals evidence—she burns it—that will clearly implicate her father in the cold-blooded murder of callous young capitalist, Harry Carson.

Yes, the victims in these crimes are bad guys—a bank and the noxious wealthy son of a capitalist. But the whole point of both novels is the Christian tenet of forgiving your enemies; Christianity is a term that was synonymous with social justice during this period. As if serious crimes weren’t shocking enough in the morally black and white 19th Century (and used as literary symbols of depravity), both Dickens and Gaskell make it extra clear to the reader that these respective crimes are “abominable.” In the case of Tom Jr.’s crime, Dickens points out that this wayward lout robbed hard-working depositors. As for the murder in Mary Barton, not only does Gaskell give us the gruesome head wound autopsy report—”they lifted up some of the thick chestnut curls, and showed a blue spot (you could hardly call it a hole, the flesh had closed so much over it) in the left temple. A deadly aim!”— but she writes about the murder in the unequivocal terms of sin.

Why then are both cover-ups presented as logically coherent givens for the protagonists, as they go unquestioned by the author and presumably, the audience.

Is the intent to foster a debate about the justness of desperate acts within a morally bankrupt capitalist society? That’d be great. But, again, in both instances, there’s no discussion of a moral conflict whatsoever—either by the narrator or in the lead character’s brain. It’s presumed without question that eluding the law by saving her brother (Loo Gradgrind in Hard Times) or father (Mary in Mary Barton) is the protagonist’s natural priority.

In Mary’s case, turning her father into the law—as he himself later intends to do—wouldn’t only match the Christian themes of the novel, but it would exonerate her lover, who is falsely accused of the crime. Gaskell, in fact, uses the evidently unthinkable option of turning over the evidence, as a binding condition that creates the literary poetics of her mental torture: visions of watching her condemned finace hang at the gallows.

The only rationale I can come up with here is that private forgiveness— that is, overlooking the crime as an extension of familial love— is more Christian than participation in the formal legal system.

Gaskell’s confusion on this point is both more palatable and more complex: The criminal in Mary Barton, Mary’s opressed, hard-working father (as opposed to the reprobrate brat in Hard Times), and the victim, a toxic playboy who not only exploits workers, but cavalierly, sexually exploits Mary herself, make the murder more comprehensible. However, the crime, cold-blooded murder (as opposed to the sneaky, sad sack theft in Hard Times) is more abhorent. This, I suppose, raises the stakes of the question itself. This story line, in turn, is a better thematic match to Gaskell’s novel, the more pensive and philosophical book of the two. And again, the stakes of the plot twist are already higher than in the Dickens novel; the question of Mary’s father’s guilt has dire ramifications for Mary’s own future in terms of her pending marriage to her lifelong friend and now fiancee, Jem Wilson. Conversely, in Hard Times, Tom Jr.’s fate is not super germane to Loo’s future, which is entwined with her spiritual comrade, former circus outcast, Sissy Jupe.

For me, the ways in which these similar plot devices differ when you game them out, serves as a symbol for how these novels are ultimately distinct. Overall, there’s more at stake in Mary Barton.

I actually got to the less-well-known Gaskell, Mrs. Gaskell, as she was known at the time, through Dickens; her name comes up in all the academic essays and intros to Dickens’ books. It turns out, Gaskell’s narrative is calmer, wiser, and has a more contemporary sensibility when it comes to the human condition.

I will say, even though, for hundreds of pages, Christian/Marxist Gaskell’s Mary Barton (1848) seems on track to be a Victorian Brit lit masterpiece, the hurried concluding chapters do trip it up a bit; they’re also marred in turn by some cheap literary symbolism (a blind character regains her sight).

That said, for 35 chapters or so (there are 38), Mrs. Gaskell is a patient, concerned, and artistic narrator, who expertly unfurls stories about star-crossed love, intimate family tragedies, potent proletarian immiseration, along with a Nancy Drew mystery to boot, complete with epistolary ciphering.

The disappointing ending is an ironic misstep because it’s here that Gaskell re-introduces the novel’s most compelling character, Esther, Mary Barton’s long lost aunt. Esther, who sets off the novel’s spiral of heartbreaks in Chapter 1 by abandoning her family to marry a soldier (not gonna happen, even though he promised), subsequently shows up in pivotal scenes as Mary’s jinxed angel. She’s an outcast, alcoholic prostitute who lives on the damp, gas-lamp streets of Industrial-Revolution-era Manchester watching over young seamstress Mary from the shadows. Unfortunately, and surprisingly, Gaskell misplays Esther’s final appearance by rushing the drama rather than taking her time with the complex character she initially created.

But my disappointment in that final turn just speaks to how invested I was in this great novel.

I savored this book; I wrote a couple of iterative takes as I lovingly read the novel throughout December and January. The tidy TV-series-wrap-up (Gaskell fast forwards a decade after the drama to a hokey scene of domestic bliss) nonwithstanding, Mary Barton brims with literary craft. Gaskell is particularly skilled at creating meaningful parallels within the natural flow of the plot, such as when Jane Wilson, busy tending to her sick sister-in law Alice, first learns that her son Jem has been arrested for murder. Stricken, she unburdens her sorrow to Alice.

Gaskell writes: “She told the unconscious Alice, hoping to rouse her to sympathy; and then was disappointed, because, still smiling and calm, Alice murmured of her mother, and the happy days of infancy.”

This knack for telling two stories at once seems to mark every scene as the novel’s main concern—owners versus workers—is replicated with binary after binary such as vengeance versus forgiveness and hope versus despair. Mary’s own story line is plagued by another stark binary: innocence versus guilt. Her lover Jem is falsely accused of murder, but again, as only she knows, it’s her beloved and morose father, mill worker John Barton, who’s guilty.

Gaskell’s poetic 19th Century prose—”the men were nowhere to be seen, but the wind appeared”—successfully immerses readers in the private worlds of her anxious characters’ inner monologues, all the while, set in the visible world of bleak lanes, cellar flats, seamstress workshops, foundry shop floors, pubs, candle-lit kitchen tables, and glimpses of the wealthy reclining on divans in the drawing rooms of their estates. The ultimate setting, however—spiraling downward in fustian rags and opium addiction toward murder—is class war.

And class analysis! In the big trial scene, wrongly accused working man Jem Wilson is defended with powerful exculpating testimony from an eye-witness sailor. When the no-expenses-spared prosecuting attorney (working for factory master Mr. Carson) cross examines, asking the sailor if he’d “have the kindness to inform the gentlemen of the jury…How much good coin of Her Majesty’s realm have you received, or will you receive, for walking up from the docks, or some less creditable place, and uttering the tale you have just now repeated…” the sailor, Will Wilson (Jem’s long lost cousin) responds with a withering juxtaposition class conscious rejoinder that exposes the unbalanced scales of justice:

Will you tell the judge and jury how much money you've been paid for your impudence towards one who has told God's blessed truth, and who would scorn to tell a lie, or blackguard any one, for the biggest fee as ever lawyer got for doing dirty work? Will you tell, sir?--But I'm ready, my lord judge, to take my oath as many times as your lordship or the jury would like, to testify to things having happened just as I said.

This is a particularly satisfying for readers to hear because we know that Mr. Carson already offered double the typical reward money (1,000 pounds as opposed to 500). And bent on vengeance, Carson told the police: "Spare no money. The only purpose for which I now value wealth is to have the murderer arrested… My hope in life now is to see him sentenced to death. Offer any rewards. Name a thousand pounds in the placards.”

By contrast, Mary got Will Wilson’s testimony through a shoe leather labor of love and not through any high-paid legal team of her own.

Meanwile, the sailor angle isn’t merely a working class plot device. It also brings the story a-train-ride-away to British port town, Liverpool, which sets the novel’s immediate Manchester-based factory strike narrative in the broader setting of national and international capitalist markets. This geographically expansive theme (again, a binary juxtaposition to Gaskell’s hyper local “Tale of Manchester Life,” the novels’ subtitle) is established early on. In addition to Mary’s patron saint Job Legh’s tragic London-based origin story (Legh is Mary’s best friend’s grandfather), and weaver union member John Barton’s eye-opening and dispiriting trip to London to plead the workers’ cause to an inattentive parliament (the weaver is also turned off by the hipster fashions), Gaskell makes it plain that forces beyond Manchester are always present.

Most prominently, Mr. Carson cuts wages to compete for “an order for goods from a new foreign market [which was] necessary to execute speedily and at as low prices as possible [because] the masters had reason to believe a duplicate order had been sent to one of the continental manufacturing towns.”

Certainly, Gaskell, who opens the novel with a comparison between the local countryside and the city, does an expert job focusing on Manchester itself, especially on its filthy gloom—a la Friedrich Engels’ influential The Condition of the Working Class in England, published in 1845, three years before to Mary Barton—penning sentences like this: “As they passed, women from their doors tossed household slops of every description into the gutter; they ran into the next pool, which overflowed and stagnated. Heaps of ashes were the stepping-stones…”

But it’s actually the climactic Liverpool chapters, when Gaskell introduces a sort of Jane Jacobs civic pride tour guide (a street-smart teenage boy named Charley who’s on a first-name basis with the Liverpool stevedores), that readers are able to place Manchester, now set in relief against its neighboring port town, fully in its own sunken context.

At both the macro and micro level, this novel lives on conjunctions like these, including my favorite passage of all, which also gives you an idea of Gaskell’s intoxicating city prose:

It is a pretty sight to walk through a street with lighted shops; the gas is so brilliant, the display of goods so much more vividly shown than by day, and of all shops a druggist's looks the most like the tales of our childhood, from Aladdin's garden of enchanted fruits to the charming Rosamond with her purple jar. No such associations had Barton; yet he felt the contrast between the well-filled, well-lighted shops and the dim gloomy cellar, and it made him moody that such contrasts should exist.

As for the social justice Christianity I noted in passing in my first sentence ^ (Christian/Marxist binary!), Gaskell rolls out this showstopping line about the evil of pursuing vengeance, which concludes a chapter titled “Murder,” symbolically transmogrifying mortal sin into a discussion about forgiveness.

Ay! to avenge his wrongs the murderer had singled out his victim, and with one fell action had taken away the life that God had given. To avenge his child's death, the old man lived on; with the single purpose in his heart of vengeance on the murderer. True, his vengeance was sanctioned by law, but was it the less revenge?

Are ye worshippers of Christ? or of Alecto?

Oh! Orestes, you would have made a very tolerable Christian of the nineteenth century!

By the way, this social justice novel also has a sense of humor. Mary’s confusion (and my own) about the “pilot-boat” plan, the mermaid story (!), and Harry Carson’s utter bewilderment at Jem Wilson’s confusing motives are just a few of the goofy moments in this wonderful book.

Bryan Washington, Lot, ©2019

Here’s another book from my own city studies seminar, Bryan Washington’s short story collection Lot, which serendipitously overlaps with a city planning, non-fiction book I read earlier this year as part of my same personalized, city syllabus: Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It. The connection between that academic book and Washington’s fast-paced story collection? The city of Houston, which Arbitrary Lines hyped as the only non-zoned city in America (you can scroll down for my review). Meanhwile, my besty Erica, who hails from Houston, recommended Washington as a talented city chronicler.

Lot, set in Houston’s cynical, hardened (and vulnerable) immigrant, POC neighborhoods—it comes with a black & white replica of the city’s street grid opposite the table of contents—revolves around Nicolás, the youngest brother in a biracial family headed by a single mom. The family is struggling to keep the restaurant they run (and live above) afloat as the the earnest mom’s incurable longing, the eldest brother Javi’s violence and reckless machismo, the distant sister Jan’s cool alienation, and the always-present subtext of Nicolás’ queer identity, along with the absentee father/husband’s ghost, haunt these stories.

The street-drug economy, the specter of homelessness, the grind of marginal jobs and petty bosses, racism, violence, and poverty also loom as a constant presence in their lives, and the lives of the characters in all the intertwined stories here, which include a few that aren’t about Nicolás’ family. Two of those stories, two of the longer stories in the collection coincidentally at 20-plus and 30-plus pages, “South Congress” and “Waugh” (all the stories here are named after Houston streets and/or districts), are explosive, showstoppers that, by stepping away from Nicolás story line, document the tenuous trappings of Nicolás’ world. “South Congress,” narrated by a young Latino named Raúl who works the drug deal circuit driving an old Corolla for his older, experienced and chatty African American mentor who sells from the open car window, and “Waugh,” narrated by a young homeless kid named Poke, who’s taken in by a Fagin figure with a flop house crew of young sex workers, amplify Nicolás’ angsty biography as Washington blurs Raúl and Poke’s pensive accounts with Nicolás’ own coming-of-age story.

While I could do with less of the tough guy dialogue throughout, Washington is an outstanding writer whose superpower is writing attention-to-detail asides—“stepping through the kitchen you cross border after border,” “we were always out of everything on the menu”— that work as slow motion metaphors for how the immediate action at hand reflects each story’s larger themes. Most often, that theme involves the idea of home and escape per the collection’s opening Gary Soto epigraph: “And how did I/Get back? How did any of us/Get back when we searched/For beauty?”

Washington, whose class-and-race-conscious immigrant narratives—a popular genre these days, particularly in poetry—stand out from many I’ve read thanks to his understated, economical prose, takes up Soto’s question head on in the story, “Elgin.” In this, the collection’s final story, Nicolás’ mother’s decision to leave Houston and move back in with her sister in Louisiana overlaps with Nicolás’ workmate Miguel’s mission to save up enough money so he can help his parents get back to their small hometown in Guatemala. “You go somewhere else and stay there and then go back home” Miguel says as the young pair, stuck in their dead end back-of-the-house restaurant jobs, ask each other why they haven’t followed their parents out of Houston.

Nicolás is the sole resident of the family house by now where “what you had to do was watch the neighborhood grow further away from you.” As in many of Nicolás stories—including a sweep of poignant childhood, tween, and teenage tales early in the collection—his quiet and nearly telepathic friendship with Miguel, who has taken the first step toward leaving town by walking out on his job after a bloody fist fight with their kitchen boss, turns into a substantive love affair. In the story’s closing scenes (and the book’s), the pair are debating staying in town or leaving as they play house in the home Nicolás family has since left behind; along with his mom’s retreat, his sister Jan has a family and home of her own, and Nicolás’ older brother Javi is dead. “You could leave. I want you to think about it, Miguel said. I want you to think about what could happen.”

Nicolás tests the question: Leaving Miguel asleep in their rumpled lovers’ bed, Nicolás suddenly drives out of town to the ocean’s edge in Galveston. “This is the furthest I’ve been from the city, my city, in years, but it doesn’t feel like anything’s changed, and honestly why would it. You bring yourself wherever you go. You are the one thing you can never run out on.”

Charles Dickens, Hard Times, ©1854

As this lively and hardly subtle novel of philosophical binaries and dramatic dialectics begins, our abandoned circus youth, Sissy Jupe, is taken from her default family of tight rope walkers, horse riders, clowns, and freaks and adopted by the stiff Gradgrind family. The Gradgrind patriarch, educator Thomas Gradgrind, commands a school (and a son, daughter, and wife too) under his strict, rationalist code. In Dickens’ comic-book parable of humanist Christianity versus conniving Capitalism, the seemingly hapless Sissy Jupe, suddenly captive in the uptight Gradgrind home, symbolizes the emotional and fanciful side of human nature. Watch out fragile Gradgrind family!

By the novel’s finale, godly Sissy and Tom Gradgrind’s pensive daughter Loo Gradgrind—initially Sissy’s standoffish counterpart, who represents the stifled side of hyper rationalism and its contorted allegiance with industrial capitalism—blur into one character. Or more accurately: Loo Gradgrind blurs into Sissy Jupe as the circus side wins the dialectic battle.

And I should clarify: Loo symbolizes the outcome of her father’s didactic code rather than representing the code itself. Brilliant, beautiful, but subconsciously longing for more as she often gazes into the fireplace (a metaphor that’s simultaneously paired with the town’s blazing capitalist smokestacks or with the fire inside her), Loo is originally incapable of love. She ends up trapped in a chilly, lifeless arranged marriage with Gradgrind’s social colleague, the bombastic banker and factory owner, Josiah Bounderby.

Loo is Incapable of love, that is, until the fragile structures of the world around her are revealed and toppled by a Rube Goldberg chain of events involving: the incorruptible laboring “Hand” Stephen Blackpool; his working class soul mate, the angelic Rachael, who should be wearing a halo; the sycophantic young bank employee, Bitzer, who we originally meet as a tattle tale teacher’s pet in Gradgrind’s school; the scheming playboy, layabout James Hartouse; the meddling Mrs. Sparsit; the hypocritical, aforementioned Bounderby; and Loo’s misguided, tragic brother Tom Jr., who’s deep in debt with a gambling addiction. The cascading story line—both dramatic and comedic—ultimately lands right back at the doorstep of the Gradgrind home in the form of Loo’s feminist monologue, which she directs at her now capsized father as the book’s final act, Book III, beings.

This pivotal confrontation follows on the heel’s of my favorite sequence here: Loo’s tour de force breakout in Book II’s closing chapter, “Chapter 12: Down,” which features her take down of arrogant trickster James Harthouse and her clever footwork outsmarting the devious Mrs. Sparsit as she makes her way home (there’s that cartoon Dickens’ symbolism again) rather than to an infamous rendezvous with Harthouse. Book II’s penultimate chapter, “Chapter 11: Lower and Lower,” is also dynamite; though, showcasing Dickens’ range, we’re treated to slapstick comedy this time as Mrs. Sparsit hides in the bushes, Shakespearean comedy style.

In the novel’s dreamy denouement, Dickens’ reverses the opening scenario: Set decades in the future, when Sissy and Loo are middle aged women, Loo is taken in by Sissy’s Jupe’s loving daughters, who symbolize the outcome of Sissy’s circus paradigm.

In a novel that’s famous for its opening paragraph, a send up of rationalism …

“Now, what I want is, facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but facts. Facts alone are wqnted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else… You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I brig up these children. Stick to Facts, Sir!”

… let me instead quote from the fanciful mirror on Dickens’ concluding page, which, formalizes the sort of Bibi Andersson/Liv Ullmann meld (a la Ingmar Bergman’s Persona) between Sissy and Loo that I noted earlier. (Coincidentally, is that Sissy or Loo on the book cover?)

Herself again a wife—a mother—lovingly watchful of her children, ever careful that they should have a childhood of the mind no less than a childhood of the body, as knowing it to be even a more beautiful thing, and a possession, any hoarded scrap of which, is a blessing and happiness to the wisest? Did Louisa see this? Such a thing was never to be.

But, happy Sissy’s happy children loving her; all children loving her; she, grown learned in childish lore; thinking no innocent and pretty fancy ever to be despised; trying hard to know her humbler fellow-creatures, and to beautify their lives of machinery and reality with those imaginative graces and delights, without which the heart of infancy will wither up, the sturdiest physical manhood will be morally stark death, and the plainest national prosperity figures can show, will be the Writing on the Wall,—she holding this course as part of no fantastic vow, or bond, or brotherhood, or sisterhood, or pledge, or covenant, or fancy dress, or fancy fair; but simply as a duty to be done,—did Louisa see these things of herself? These things were to be.

This is obviously a fun and tidy book. But two objections, one minor, and one major. First, the gripe. It’s a bit incongruous that Thomas Gradgrind and Loo aid and abet wayward Tom Jr. after they have rejected the nihilism at the heart of industrial capitalism. I understand that assisting Tom Jr., despite his crimes, could be read as placing the amorphous bonds of family over the rational rule of law—and even seen as a Christian gesture of forgiveness that follows the the gospel of martyred working man Stephen Blackpool who preaches forgiveness in his death bed monologue. But to me, it reads more as an endorsement of cynicism.

My bigger complaint is about the standard Christian populism at the heart of this novel. While meant as an endorsement of brotherly Socialism, it’s not dissimilar to the simplistic Fight Club reactionary utopian-ism that often ends up scripting fascist Year-Zero purity politics of holier than though crusades for authenticity. Watch out, fragile Jupe family.

I trust Dickens, but his quaint style of moralism can quickly give way to the Huey Longs and George Wallace’s of the world. Interestingly, Hard Times itself features a character who fits this exact mold: Slackridge, the “United Aggregate Tribunal” (LOL) union demagogue that Dickens spoofs in Book II, “Chapter 4: Men and Brothers.” Here, Slackridge turns the workers against their factory brother, good guy Stephen Blackpool.

Betty Smith, Tomorrow Will be Better, ©1948

This is the follow-up to Smith’s blockbuster classic, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. It’s not literally a Part Two, but all eyes were on Smith after her mega-hit debut. This 1948 novel, published five years after A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, drops the reader into the same bittersweet pre-war Brooklyn universe of struggling, working-class Irish and Italian, first-generation immigrant families who are caught on the treadmill of menial labor, tight budgets, spent, loveless marriages, and fumbling young overtures. Set in class-and-race-conscious 1920s Williamsburg and Bushwick where fathers approve of suitors simply if they vote a straight Democratic ticket and street peddlers double as philosophers, the novel mostly takes place in spare flats over meager family dinners in between lives lived watching the clock at work (or gossiping in the lady’s washroom), riding home on crowded streetcars, haggling with (though more often bonding with) proprietors of corner shops, bakeries, and laundries, and occasionally dressing up for a Friday night dance. Differentiating itself from A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Tomorrow Will be Better leans more into the bitter side of bittersweet.